The Amos Farm

How Christian’s front yard ignited a fight for social justice

by Christian Torp

Legal disclaimer: Nothing in this article is legal advice. Seek the assistance of an attorney in your jurisdiction. The author is NOT an attorney in Maine.

The revolutionary front yard has gone on the offensive. It wasn’t planned, but I couldn’t have hoped for such a perfect legal storm…

My front yard is a community garden. A few years back college spring break programs de-sodded our lawn and we began planting crops there. Furthermore, we let whomever may want to pick from the fruit of the land.

Sure, folks have ripped out entire plants and done other damage. But so it goes… You can’t steal what’s free.

Beyond that, I’m an avid gardener interested in sustainability, and I’m a radical Christian having come to the faith later in life. In my Bible reading I’ve discovered that it spells out a fertility enhancement of sorts. Productive land is to be given its Sabbath rest every seven years. What a plan! Increasingly, we are learning that the traditional ways might not have been so bad after all. Given the destruction modernity has caused, the ancients might’ve had better ideas all along.

On our three front plots (front yard, split by a walkway and one side of the utility strip) I planted on one side and ran out of plants before arable land. So, both the largest of the two front areas and the utility strip were left unperturbed.

By June our front yard was reminiscent of an African savanna.

A six-foot Polk Berry spread its limbs to offer cats and squirrels shade beneath its branches and in the inches of growth below it. But those inches began to catch up. At first four-foot posts prevented the aggravation of passersby having to move prairie out of their way, but by July seven-foot tee posts replaced them. And by August, school children and grannies were shaded from the sun beneath the weedy overhang.

I’d done the research. I knew that local code prohibited anything “other than crops, trees, bushes, flowers or other ornamental plants, [from growing] to a height exceeding twelve (12) inches anywhere.” And from my activism I knew that a religious freedom bill had passed in Kentucky, a law that should be called the freedom to discriminate bill. What an awesome circumstance, using a law intended to discriminate as a defense against the city mandating tidy front yards.

But nothing happened, for months, until finally…

On September 8th I was cited for “Trash and Debris” (no explanation given) and “Weeds/High Grass – Must Not Exceed 12 High mainly front yard.”

On September 15th I appealed and was set to be heard Monday, October 10th at 1 p.m. (Note this example of American classism. If you disagree with Code Enforcement, whatever the reason, however wrong they may be, your only option is to randomly have assigned to you a hearing in the middle of the day on a workday.) How many non-professional workers have the option to skip work, not to mention the financial cushion needed to lose that pay?

The hearing was a trip.

The freedom of religion law was to be my defense. After all, the Bible calls for productive land to have its Sabbath rest.

The hearing officer had lobbied for the freedom of religion law. So how could things go wrong? Several times during the hearing he even said, “Obey God, not man.” Nonetheless, he found against me, writing “no cover crop over 12 inches in right of way” and “any crops WITHIN THE ORDINANCE in the front yard.”

Of course, “crop” is not once defined in the local code. Additionally, the enforcement officer said during the hearing that he had no authority regarding the utility strip, the very reason they ruled on the “right of way.”

Once again, I’d done the research, not just in terms of my defense, but my appeal rights too. I knew that an appeal went to a real court, before a real judge with a real jury. Furthermore, this case was a de novo review, “a new thing.”

The local ordinance defies state law in regards to appeal deadlines (10 days v. 30 days) and is generally vague. I’m told to only grow “crops within the ordinance,” but the ordinance doesn’t define “crop.” Better still, the violation I committed was “tall grass and weeds Lambs-Quarters weed/edible.” But, lambs quarter is extensively cultivated and consumed in Northern India as a food crop. Crops are legal. Even better, as code enforcement is given no training on plants, they asked our local Extension Horticulturalist for information. The day after my hearing I called him up and he told me that all he had done was forward code enforcement some info, which they misrepresented to the hearing officer.

And then it gets really good.

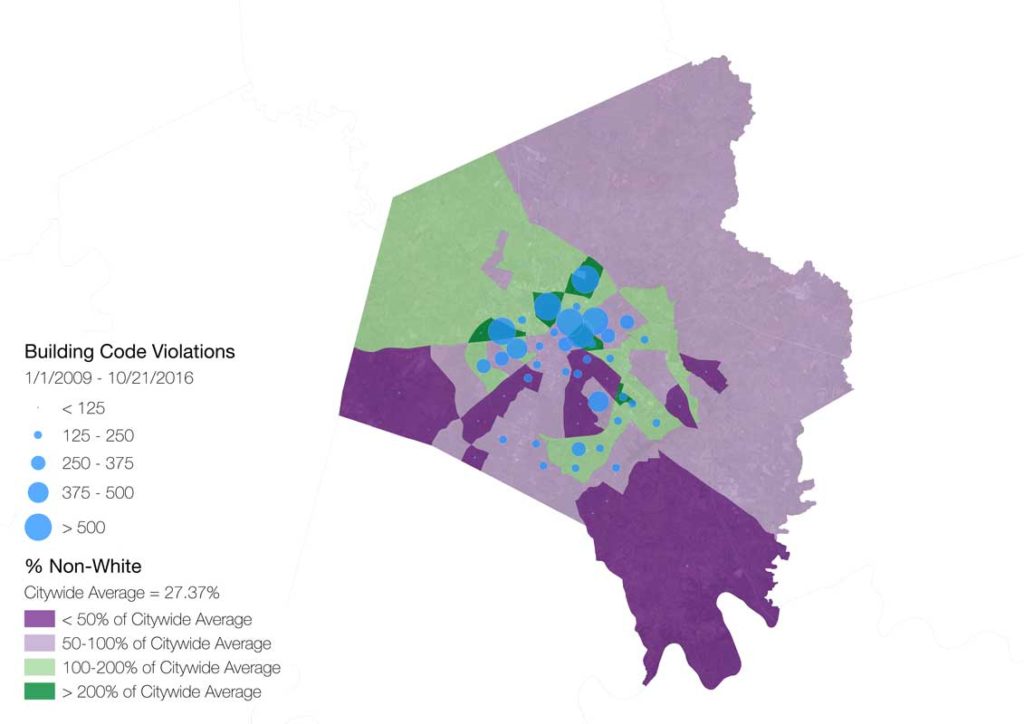

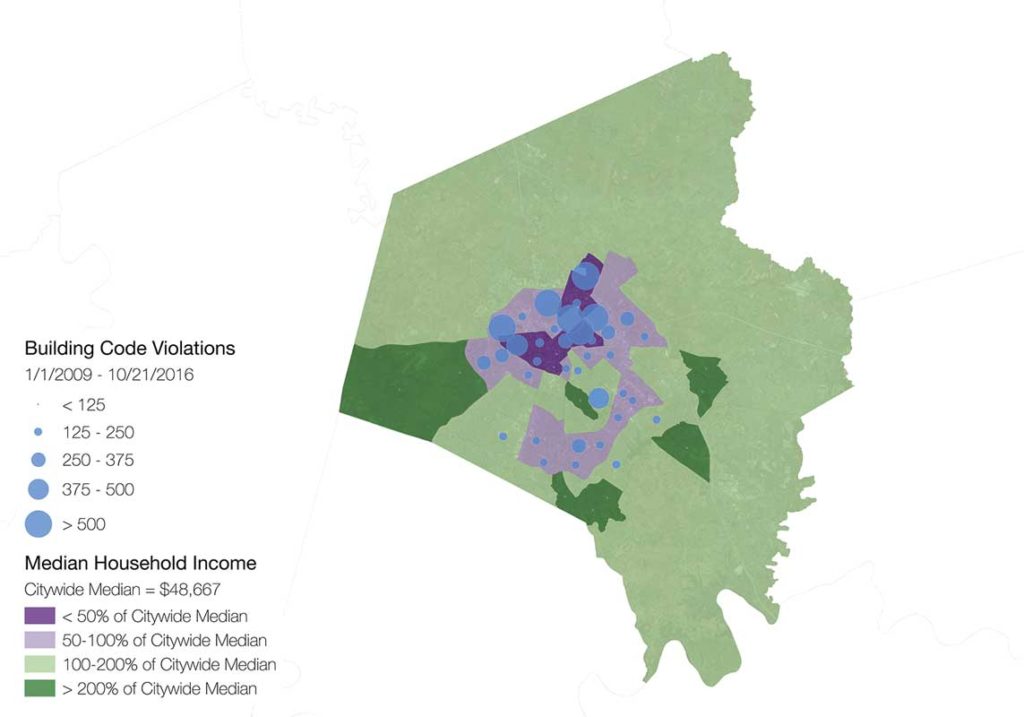

You see, an appeal of code enforcement in Kentucky is a new thing, so I could use anything in my defense. Sure, the local code is in violation of Kentucky’s Religious Freedom Restoration Act, but in the discriminatory and racist way it is enforced it is also in violation of the U.S. Civil Rights Act and the Kentucky Civil Rights Act. Moreover, we’ve enlisted the help of some geographers at the local college who could give us definitive geographic, visual proof of the racist application of code enforcement.

ABOVE: Map of Lexington code enforcement created by University of Kentucky students shows density of violations in areas where residents earn below citywide median income. BELOW: Map of code violation density in areas with large non-white residents. -Courtesy of Christian Torp

The filing fee for my appeal is a pittance compared to what it’s going to cost the City of Lexington. It might be unobtainable for my neighbors suffering under the weight of gentrification, but I can swing it.

I’m writing for an audience in Maine, not Kentucky. But I hope you can learn from this example of using the system against itself. Moreover, knowledge is power and I’ve done nothing you can’t do for yourself. While I may be an attorney, you are free to defend yourself and file your own cases without any legal training pro se (for oneself). The only way I’m different is that I can do it for others.

Tune into The Amos Farm next month for how you yourself can use the legal system against the old forces for a sustainable future.