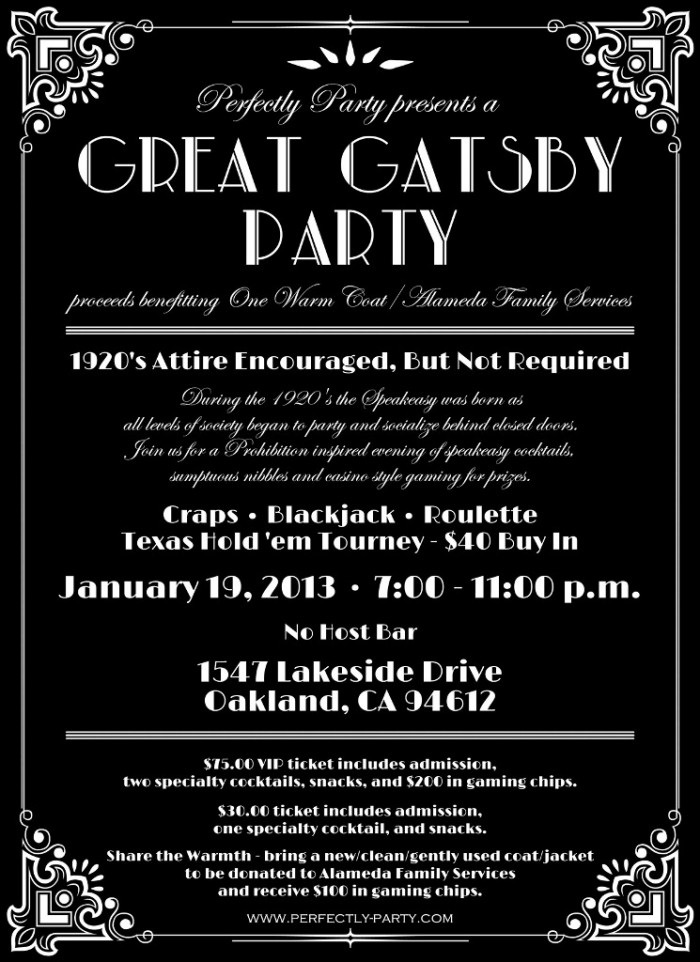

An advertisement for a “Great Gatsby”-themed party in Oakland, CA.

Adam Marletta

As we continue our societal shift from a print-based culture which emphasizes the importance of reading, fact-based reporting, and critical thinking, to one dominated by images, we seem to be losing our appreciation for, among other things, irony.

Case in point is Pride Portland! which kicks off its annual gay pride celebration week June 12 with a Great Gatsby party at Grace Restaurant.

A Gatsby-themed party, for those unfamiliar with the newly emergent phenomenon, is exactly what it sounds like. Attendees dress either as specific characters from F. Scott Fitzgerald’s classic novel, The Great Gatsby, or in 1920s “Jazz Age” themed attire. (Expect to see lots of ladies dressed as “Flappers.”)

The parties themselves are designed to be extravagant, over-the-top affairs, inspired by Jay Gatsby’s gala parties which he throws every weekend in the novel.

The problem with holding decidedly un-ironic Gatsby-style celebrations of greed and hedonism should be evident to anyone remotely familiar with the book. Gatsby’s parties are ultimately empty, self-indulgent affairs. Fitzgerald’s scathing portrayal of the ultra-rich is meant to highlight the utter depravity of their decadent lives. He certainly did not intend for anyone to admire–let alone emulate–their consumerist debauchery.

As Atlantic writer, Zachary M. Seward observes in a 2013 piece titled, “The Sublime Cluelessness of Throwing Lavish Great Gatsby Parties, “It’s like throwing a Lolita-themed children’s birthday party.”

Put simply, anyone attending one of these parties who claims to have any sort of affection for The Great Gatsby needs to go back and re-read the book. (And I am keeping my focus here strictly on the novel–not Baz Luhrmann’s overwrought 2013 film adaptation which, with its anachronistic hip-hop soundtrack and shameless Brooks Brothers product-placement, largely misses the point.)

Make no mistake: The Great Gatsby is a searing anti-capitalist polemic. Your high school English teacher likely did not explicitly present it as such, but that is only because she feared doing so would brand her a “political” educator, and risk her job.

Fitzgerald, along with other early 20th century American authors like John Steinbeck, Sinclair Lewis, Jack London, and Upton Sinclair, used his literary talents to call attention to social ills and injustice.

Like our modern day Wall Street speculators and hedge-fund swindlers, Gatsby derives his massive wealth through fraud, theft, organized crime, and the novel darkly hints, even murder. Gatsby is meant to symbolize the rise of the post-World War I “new rich,” which populate the fictional Long Island town of West Egg. Unlike the “old wealth” aristocrats of East Egg, Gatsby and his ilk represent the risk-taking, self-starting entrepreneurs, which Ayn Rand would go on to canonize as the undisputed economic drivers of society (the so-called “job creators”) a quarter of a century later.

As such, Fitzgerald imbues Gatsby’s self-made “re-birth” with an almost messianic quality. He writes:

The truth was that Jay Gatsby, of West Egg, Long Island, sprang from his Platonic conception of himself. He was a son of God–a phrase which, if it means anything, means just that–and he must be about His Father’s business, the service of a vast, vulgar, and meretricious beauty. So he invented just the sort of Jay Gatsby that a seventeen year old boy would be likely to invent, and to this conception he was faithful to the end.

But Gatsby is ultimately a fraud.

In his pursuit of wealth, privilege, and social status (all the superficial elements of the so-called “American Dream”) he erases his true identity. He becomes a hollow shell of a man, incapable it seems, of truly experiencing the love and human connection–as symbolized in the character of Daisy–he so desperately desires.

Despite his grand wealth and near-legendary reputation, Gatsby remains unfulfilled. He, like the novel’s protagonist and narrator, Nick Carraway, is bored and alienated, restlessly scurrying from one debauched party to the next.

“I was within and without,” Nick recounts, “simultaneously enchanted and repelled by the inexhaustible variety of life.”

How any of this pertains to LGBT activism is beyond me. Indeed, not only does this choice of event seem completely arbitrary, it also furthers the implicit attitude that, in the wake of the now 37 states (including Maine and the District of Columbia) that have legalized gay marriage, the major work of the LGBT movement is, if not completely finished, at least has an aura of inevitability.

This is in no way meant to diminish the significance of these historic victories. But LGBT liberals’ preoccupation with marriage–often at the expense of broader gay rights and social justice issues–has always struck me as severely myopic. To wit, according to a 2014 Guardian op-ed, nearly 40 percent of America’s homeless youth identify as LGBT, yet the movement has overwhelmingly focused its money and resources on securing marriage rights.

The fact that this year’s Pride! events are sponsored by “Too Big to Fail” banks like Bank of America and TD Bank, along with U.S. Cellular, Hannaford, and many of the same restaurants and “small” businesses that adamantly oppose the Green Party’s campaign to raise Portland’s minimum wage to $15 an hour, does not help matters.

This situation reveals the limits of so-called “identity politics.” The left’s lack of a class-orientation aimed at dismantling capitalism prevents it from mobilizing as a united whole. While the various struggles for gender, racial, and LGBT equality are crucial for establishing any sort of socialist democracy, those battles cannot exist within a vacuum. They cannot, in other words, become an end in of themselves.

All art, according to James Baldwin, is a “kind of confession.”

“All artists, if they are to survive,” he wrote, “are forced, at last, to tell the whole story; to vomit the anguish up.”

When we trivialize art and literature we lose sight of the profound messages and convictions the artists struggle to convey. We need to rediscover those urgent messages–lest we all succumb to the nonstop orgy-porgy of an insipid commercial culture.

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that the Portland-based LGBT advocacy group, Equality Maine, and Pride Portland! are the same organization. They are, in fact, two different groups. The confusion stems from the fact that the Equality Maine logo is prominently featured right above Pride Portland!’s on the Pride website. The summary explaining that EQ ME is the “nonprofit fiscal sponsor” for Pride Portland! under the site’s homepage was not present when the original version of this column was posted. Thus, the confusion. The author regrets the error and has corrected it.

Adam Marletta, WEN Political Commentator

Lost in Translation: Why I Won’t Be Attending Your “Gatsby” Party

An advertisement for a “Great Gatsby”-themed party in Oakland, CA.

Adam Marletta

As we continue our societal shift from a print-based culture which emphasizes the importance of reading, fact-based reporting, and critical thinking, to one dominated by images, we seem to be losing our appreciation for, among other things, irony.

Case in point is Pride Portland! which kicks off its annual gay pride celebration week June 12 with a Great Gatsby party at Grace Restaurant.

A Gatsby-themed party, for those unfamiliar with the newly emergent phenomenon, is exactly what it sounds like. Attendees dress either as specific characters from F. Scott Fitzgerald’s classic novel, The Great Gatsby, or in 1920s “Jazz Age” themed attire. (Expect to see lots of ladies dressed as “Flappers.”)

The parties themselves are designed to be extravagant, over-the-top affairs, inspired by Jay Gatsby’s gala parties which he throws every weekend in the novel.

The problem with holding decidedly un-ironic Gatsby-style celebrations of greed and hedonism should be evident to anyone remotely familiar with the book. Gatsby’s parties are ultimately empty, self-indulgent affairs. Fitzgerald’s scathing portrayal of the ultra-rich is meant to highlight the utter depravity of their decadent lives. He certainly did not intend for anyone to admire–let alone emulate–their consumerist debauchery.

As Atlantic writer, Zachary M. Seward observes in a 2013 piece titled, “The Sublime Cluelessness of Throwing Lavish Great Gatsby Parties, “It’s like throwing a Lolita-themed children’s birthday party.”

Put simply, anyone attending one of these parties who claims to have any sort of affection for The Great Gatsby needs to go back and re-read the book. (And I am keeping my focus here strictly on the novel–not Baz Luhrmann’s overwrought 2013 film adaptation which, with its anachronistic hip-hop soundtrack and shameless Brooks Brothers product-placement, largely misses the point.)

Make no mistake: The Great Gatsby is a searing anti-capitalist polemic. Your high school English teacher likely did not explicitly present it as such, but that is only because she feared doing so would brand her a “political” educator, and risk her job.

Fitzgerald, along with other early 20th century American authors like John Steinbeck, Sinclair Lewis, Jack London, and Upton Sinclair, used his literary talents to call attention to social ills and injustice.

Like our modern day Wall Street speculators and hedge-fund swindlers, Gatsby derives his massive wealth through fraud, theft, organized crime, and the novel darkly hints, even murder. Gatsby is meant to symbolize the rise of the post-World War I “new rich,” which populate the fictional Long Island town of West Egg. Unlike the “old wealth” aristocrats of East Egg, Gatsby and his ilk represent the risk-taking, self-starting entrepreneurs, which Ayn Rand would go on to canonize as the undisputed economic drivers of society (the so-called “job creators”) a quarter of a century later.

As such, Fitzgerald imbues Gatsby’s self-made “re-birth” with an almost messianic quality. He writes:

But Gatsby is ultimately a fraud.

In his pursuit of wealth, privilege, and social status (all the superficial elements of the so-called “American Dream”) he erases his true identity. He becomes a hollow shell of a man, incapable it seems, of truly experiencing the love and human connection–as symbolized in the character of Daisy–he so desperately desires.

Despite his grand wealth and near-legendary reputation, Gatsby remains unfulfilled. He, like the novel’s protagonist and narrator, Nick Carraway, is bored and alienated, restlessly scurrying from one debauched party to the next.

“I was within and without,” Nick recounts, “simultaneously enchanted and repelled by the inexhaustible variety of life.”

How any of this pertains to LGBT activism is beyond me. Indeed, not only does this choice of event seem completely arbitrary, it also furthers the implicit attitude that, in the wake of the now 37 states (including Maine and the District of Columbia) that have legalized gay marriage, the major work of the LGBT movement is, if not completely finished, at least has an aura of inevitability.

This is in no way meant to diminish the significance of these historic victories. But LGBT liberals’ preoccupation with marriage–often at the expense of broader gay rights and social justice issues–has always struck me as severely myopic. To wit, according to a 2014 Guardian op-ed, nearly 40 percent of America’s homeless youth identify as LGBT, yet the movement has overwhelmingly focused its money and resources on securing marriage rights.

The fact that this year’s Pride! events are sponsored by “Too Big to Fail” banks like Bank of America and TD Bank, along with U.S. Cellular, Hannaford, and many of the same restaurants and “small” businesses that adamantly oppose the Green Party’s campaign to raise Portland’s minimum wage to $15 an hour, does not help matters.

This situation reveals the limits of so-called “identity politics.” The left’s lack of a class-orientation aimed at dismantling capitalism prevents it from mobilizing as a united whole. While the various struggles for gender, racial, and LGBT equality are crucial for establishing any sort of socialist democracy, those battles cannot exist within a vacuum. They cannot, in other words, become an end in of themselves.

All art, according to James Baldwin, is a “kind of confession.”

“All artists, if they are to survive,” he wrote, “are forced, at last, to tell the whole story; to vomit the anguish up.”

When we trivialize art and literature we lose sight of the profound messages and convictions the artists struggle to convey. We need to rediscover those urgent messages–lest we all succumb to the nonstop orgy-porgy of an insipid commercial culture.

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that the Portland-based LGBT advocacy group, Equality Maine, and Pride Portland! are the same organization. They are, in fact, two different groups. The confusion stems from the fact that the Equality Maine logo is prominently featured right above Pride Portland!’s on the Pride website. The summary explaining that EQ ME is the “nonprofit fiscal sponsor” for Pride Portland! under the site’s homepage was not present when the original version of this column was posted. Thus, the confusion. The author regrets the error and has corrected it.

Adam Marletta, WEN Political Commentator