Spare the Woodman’s Axe

Heritage Tree Ordinance to Protect Urban Trees

By Tony Zeli

A new ordinance in the City of Portland makes it harder for private property owners to chop down large, healthy trees. But it allows emergency waivers and tree removal permits. City Arborist Jeff Tarling believes the new heritage tree ordinance is the first of its kind in northern New England, although Massachusetts and Connecticut have had such ordinances for many years.

What the heritage tree ordinance does and doesn’t do

If you have a big tree in your neighborhood that you love, you may think it’s protected. Think again. The ordinance prevents the removal of any “heritage tree” on private property but only within historic districts. Also, it may be relatively simple to get a permit granting permission to swing the axe.

A “heritage tree” is a tree located on privately owned property and located in a designated historic district. They include large shade trees of 24 inches in diameter when measured at breast height. Also included are ornamental trees that measure 12 inches in diameter at breast height. They include trees on the state’s Register of Big Trees (known as the “Big Tree List”) and native trees that are rare or threatened.

A property owner can obtain a permit from the parks department to remove a heritage tree. The city arborist approves the permit if there is a plan to replace it or if applicants pay into a tree trust for planting and maintaining city trees. If the property owner plans to replace it, then replacement trees must be of the same or similar species and size. However, there are exemptions if trees are unavailable. In such a case, the property owner can replace the tree with a greater number of smaller trees.

And in case of a tree that poses a risk to safety, the city arborist may give immediate authorization to remove it. Likewise, during severe weather or emergencies.

Big role for the city arborist

The ordinance places a lot of responsibility on City Arborist Jeff Tarling. When asked if he had the staffing to properly implement the ordinance, Tarling was hopeful.

“We have asked for some additional funding to support staff to inspect and evaluate trees that are affected by the new ordinance,” said Tarling. “We are working on promotional and media information for both property owners, commercial arborists, and the public.

“Overall, we think this is a good first step to protect Portland’s heritage trees. I think we can thank our citizenry and [Portland] City Council who supported this effort and the past unknown tree planters [who] have cared enough to plant these beautiful trees often a century ago – to this we are also honoring them. Of course, this is why Portland has been known as ‘the Forest City’ since the early 1800’s. Trees are part of Portland’s fabric; it has always been that way…”

Denuding of the ‘Forest City’

Captain George H. Preble undertook the first known tree survey in Portland in 1854. He claimed to have walked every one of Portland’s approximate 134 streets and lanes to count each of Portland’s 3300 trees.

In Preble’s own telling of his perambulating journey through Portland (as recorded in “History of Portland,” by William Willis, 1864), Preble noted State, Danforth, and Cumberland as “beautifully embowered” by trees. He counted no more or less than 301 trees along Congress Street alone. Preble concluded, “…through the whole period of our history, Portland properly has been called the ‘Forest City.’” That was in 1854.

Fast forward to June 2020. While thousands of Portlanders joined the rest of the nation mourning George Floyd, a much quieter protest began in the West End over the removal of trees.

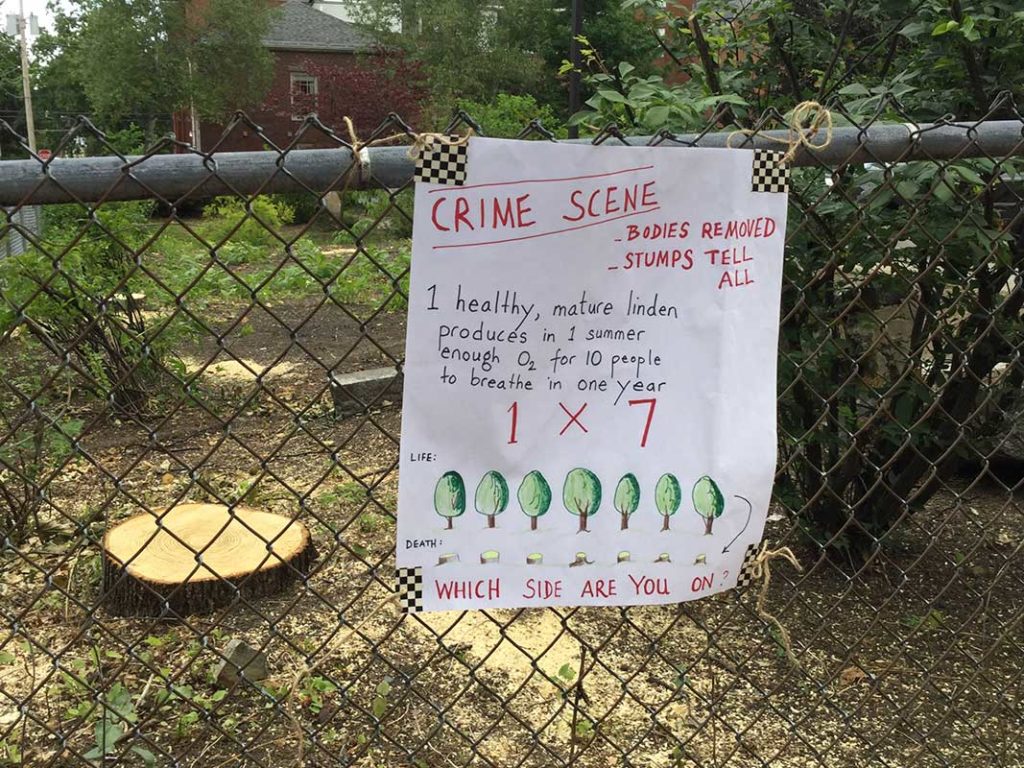

On a lot on the corner of Park and Gray Streets, seven healthy, mature linden trees—deciduous trees with heart-shaped leaves—were cut down. Many of the larger trees were reportedly two to three feet in diameter.

Distraught neighbors protested and hung signs on fencing along the property. They read: “Where did the trees go?” and “CRIME SCENE.” Property owners promptly removed the signs. Protesters replaced them with skull and crossbones and more signs. It went on for weeks.

Theses weren’t the first trees to go down. West End community members (including members of Portland Climate Action Team who submit The West End News “Bright Ideas” column) began to wonder if our “Forest City” could remain such for very much longer.

No one was counting

Although Capt. Preble isn’t counting trees today, it is clear that the number of trees cut down in the West End over the past handful of years is staggering. Neighbors saw huge trees behind the Precious Blood Monastery on State Street get the ax (2019).

Before that, a homeowner’s association took down several large trees along Clark Street (2018). The HOA felled the trees to fulfill a city parking space requirement for a development on Brackett Street. A nearby resident, who had walked under the huge trees twice a day, awoke one morning and found herself “shocked” by the scene.

A few years farther back, a huge stretch of undeveloped land along West Commercial Street experienced a clear cutting (2015). Owners did this to prevent camping by un-housed persons.

Another example is Elm Terrace on the corner of High and Danforth Streets. It had been a green space with huge white pines. Many enjoyed the pines with great pride until they came down for redevelopment. Off Danforth Street a row of dead pines and pine stumps… A large tree near Spring and High… And so it goes…

Extolling the benefits of trees

It’s not just about losing beautiful trees and cooling shade. As one of the protest signs along Gray Street read, “1 healthy, mature linden [tree] produces in 1 summer enough 02 for 10 people to breathe in one year.”

Trees are good for the environment, raise land values, and provide habitat for animals. The heritage tree ordinance is intended specifically to clean the air, reduce runoff (a mature tree can store 50 to 100 gallons of water during large storms), and sequester carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Trees also reduce the urban heat island effect, cooling the air and literally making the city more livable.

For all they do for us, a handful of West End residents and others took the lead and worked with city staff and councilors to protect the trees.

Activists want more from the heritage tree ordinance

Yes, the heritage tree ordinance is a potential hurdle for those looking to develop property. But the most intriguing opposition comes from groups who support the ordinance. They seek to protect more trees across the whole city.

Portland Protectors, the group that pushed for the city’s pesticide ordinance gave the following statement:

We applaud the City Council for taking steps to protect the city’s trees. However, we see the Heritage Tree Ordinance as an inequitable ordinance that leaves most city trees and most city neighborhoods with no protection. In a time when policy makers are being asked to undo systemic racism and injustices in public policy, it’s particularly troubling that the city would adopt a policy that provides greater environmental protection for some of the city’s wealthier neighborhoods while denying those same environmental protections in other neighborhoods.

-Avery Yale Kamila, Portland Protectors

Portland Protectors say the heritage tree ordinance leaves most trees with no protection. Also, there is no citizen oversight, unlike the pesticide ordinance which has a citizen committee overseeing waivers. Here, city staff have full purview over reviewing applications and granting waivers.

“The ordinance contains so many loopholes, we suspect it is unlikely to stop the removal of most trees in Historic Districts,” said Portland Protectors co-founder Avery Yale Kamila.

“Loopholes included in the ordinance allow heritage trees to be cut when they will be replaced by new trees, when the property owner makes a payment, or when the property owner can demonstrate financial hardship.”

Necessary first step

Liz Parsons, one of the West End residents who pushed for this ordinance, encouraged others to view it as a necessary first step.

“All members of the Sustainability and Transportation Committee have said they want the ordinance expanded beyond the historic districts. But they began with something they thought could pass fairly easily, could be learned from once implemented, and subsequently improved…” said Parsons.

Councilors Spencer Thibodeau and Belinda Ray from the Sustainability Committee echoed this sentiment as they voted to pass the ordinance at their early August city council meeting. At that same meeting, Councilor Tae Chong called the ordinance a “pilot program.”

Ultimately, the new heritage tree ordinance is one step, and maybe not the last, to protect trees in a city that has long done so. Consider the Deering family, who donated Deering Oaks Park to Portland. They decreed “spare the woodman’s axe,” to save their beloved White Oaks. Many of which still stand today, a century and a half later.

Tony Zeli is publisher and editor. Reach him at thewestendnews@gmail.com.

1 Comments

Pingback: Preserving the Forest City with the Heritage Tree Ordinance - The West End News