The Amos Farm

Vegetable Storage

by Christian Torp

Recent attempts to consolidate assessments of the effects of human activities on stratospheric ozone (O3) using one-dimensional models for 30∘ N have suggested that perturbation of total O3 will remain small for at least the next decade. Results from such models are often accepted by default as global estimates. The inadequacy of this approach is here made evident…–Nature, May 16, 1985: “Large losses of total ozone in Antarctic reveal seasonal CIOx /NOx interaction”

Before we get to vegetable storage I want to ask, do you remember the “hole in the Ozone Layer?” If you do, you’re showing your age. The above quote is from the paper that exploded into the media back in the mid-eighties. That story, as opposed to the likely ending of today’s Climate Change debate, had a happy ending.

Recent measurements taken from the South Pole have shown that the O3 concentration is increasing and the “hole” is closing, and it is all thanks to the 1987 Montreal Protocol. This international agreement not only was legally binding, but also it could be accomplished with far, far less industry investment than even the modest reductions in CO2 emissions called for under the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement. Although, that agreement will still lead to an increase of three degrees Celsius even if every signatory meets or exceeds their non-binding promises.

Back to Vegetable Storage

Historically humans survived non-productive seasons by altering their diet to accommodate what was available and artificially limiting the growth of bacteria in the food they had accumulated. This was accomplished through drying, salting, sugaring, pickling, smoking, canning, burial, fermenting and, to a limited degree, cooling.

Drying: Humans have been preserving food for 14,000 years through this means. Drying may be accomplished by placing food in an area with high heat and airflow, and low moisture and light. But it all depends on what you’re trying to dry. For instance, cayenne peppers need only be strung and hung in a window, while tomatoes will require tremendous amounts of all necessary conditions.

Salting/Sugaring: Similar in effect to drying the salt/sugar draws moisture from the food being stored (think ham).

Pickling: Preserving food in an antimicrobial liquid, either chemical (cucumbers, corned beef, herring) or fermented (sauerkraut, kimchi).

Smoking: Exposing the food to burning plant material thereby depositing numerous pyrolysis products into the food both drying and preserving it.

Canning: Cooking the food within sealed, sterile containers to kill or inhibit any bacteria contained within.

Burial: Preserving foods by inhibiting bacterial growth through low light and oxygen, cool temperatures and soil Ph, desiccant ability.

Fermenting: The introduction and cultivation of microbes that inhibit dangerous microbes through competition and the creation of acids or alcohol which inhibit the growth of all microorganisms.

Root Cellar: A specific, domestic location for maintaining low temperature and constant humidity for food storage.

Freezing: Not a traditional method of food storage in most cultures and not all foods freeze well. And there are the tangential environmental repercussions. USDA on freezing food: fsis.usda.gov/wps/portal/fsis/topics/food-safety-education/get-answers/food-safety-fact-sheets/safe-food-handling/freezing-and-food-safety/CT_Index

Here’s to preserving your harvest!

- Use tested, peer reviewed methods. When searching online use only trusted sources or add “extension” to your search terms.

- Know the recommended humidity for what you’re storing.

- If you’re not sure, if something seems wrong… DO NOT eat it. Compost it.

- Follow recipes and directions EXACTLY.

- Save and preserve only the best, most unblemished fruits of your labors.

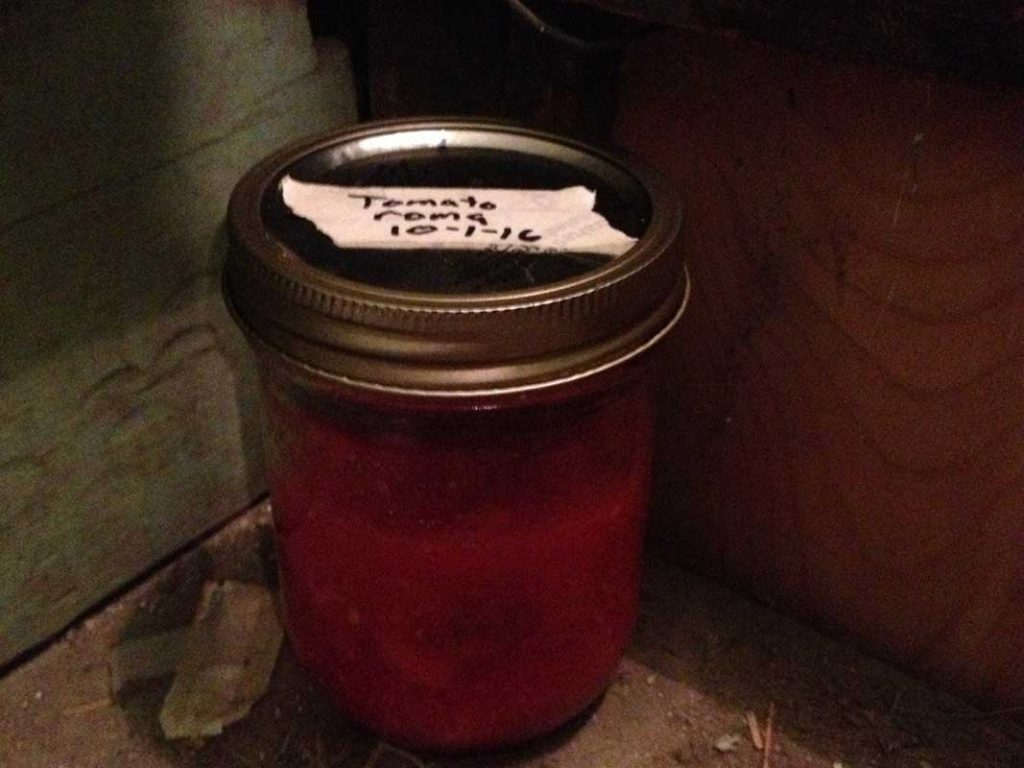

- Date EVERYTHING. If it’s been a year, into the compost it goes.

What to make of all this rambling? As I said in the second installment of Amos Farm in the December 2015 issue, “On Designing an Urban Ag System,” preserving your food depends first and foremost on what you like to grow and eat. For instance, sweet potatoes might be an awesome crop and store longer, at a higher temperature and at lower humidity than a lot of things. But if you don’t like them, than what good is that?

Once you’ve decided what you’re hoping to store, determine the requirements of that crop and see if it’s a possibility. If it is, work on creating the environment or obtaining the equipment required to properly preserve that item. Love butternut squash? Then you’d better not let the temperature get below fifty degrees, and the humidity should be only moderate, but you won’t need any equipment more sophisticated than a basement. While if it is tomatoes that you love, then you’d better look into canning or freezing, and be mindful of the expense and equipment that requires.

Best of luck!

Resources

National Center for Home Food Preservation: nchfp.uga.edu

UMaine publication on Fruit and Vegetable Storage: extension.umaine.edu/publications/4135e

University of Minnesota Extension on freezing foods: extension.umn.edu/food/food-safety/preserving/freezing/the-science-of-freezing-foods

Christian L. Torp

Christian is an attorney, missionary, activist, urban-farmer and advocate for social change who lives at Justice House (Facebook: Justice House) with his wife, Tanya in Lexington, KY. If you have any questions or comments for Christian, or there’s something you’d like to know more about, please reach out to him at theamosfarm@gmail.com.