by Tony Taylor

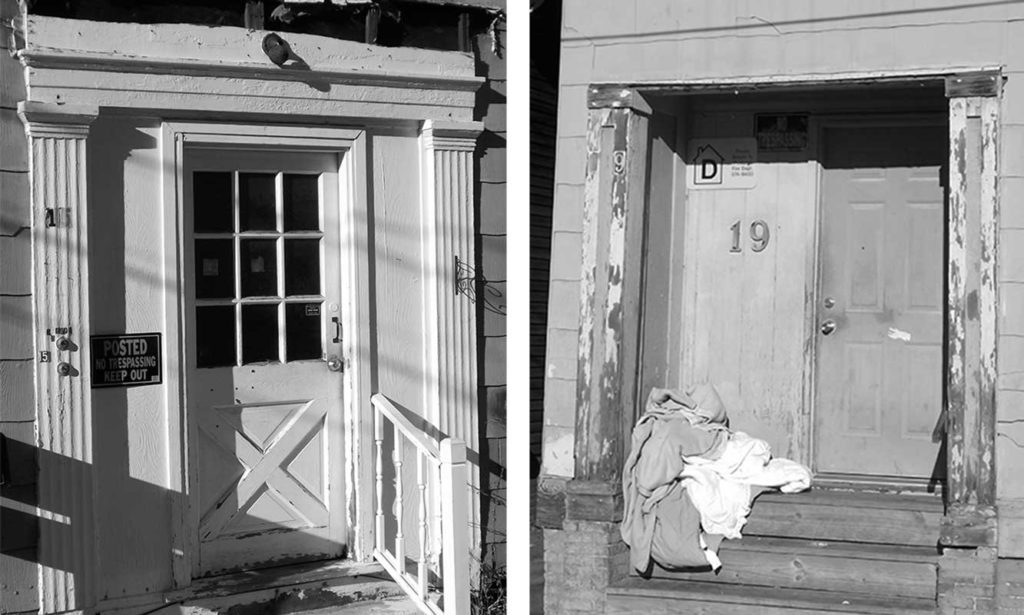

Two Chestnut Street doorways with missing trim: (Left) Cuts in siding show outline of missing cornice on fine Chestnut Street doorway. (Right) Recessed Greek revival doorway with missing cornice is popular Chestnut Street homeless hangout. -Photos by Tony Taylor

As a teenage student of architectural history in late 60’s Connecticut, I remember my excitement at finding and photographing a row of mill houses in Willimantic that had been documented in a black and white photo by famed WPA Art Projects photographer Walker Evans. I found some similarities, as well as striking differences in how the scene looked then and now. The houses were still there, unmistakable in their even spacing and matching rooflines. But in Evans’ ‘30’s photo, the houses had the uniform stamp of 19th century mill town ‘corporation houses’ – each with the same good architectural manners – white clapboard walls and crisp Greek revival trim accenting projecting entrances and gables.

The corporation houses had been sold off by the mill to individual buyers in the 50’s. By now much of the old neighborhood’s once-unified look was gone, varied now by random remodeling by the new owners. New siding, windows, doors went on many houses. Only by noting an unchanged entrance on one or another that still had its old windows, could one imagine what the neighborhood once looked like.

Often when I’ve driven past a house with an iconic Maine look — say, a Cape with an entrance with a naïve interpretation of Greek key pilasters that I recognized from an Asher Benjamin 1840’s builder’s guide, or a simple Cape connected to a barn with a long, low ell — I’d make a mental note to return to take a photo. Only when I returned, I would often as not find something had changed and spoiled the scene. The doorway now had its sidelights boarded over or shortened, or the house with the low ell now sported a camel’s hump of an addition where the connecting ell had been.

Writing in 1957, Julian Huxley warned of “economic and social pressures which are forcing mass-produced goods into every corner of the globe … sapping ancient cultural ideals and destroying traditional art and craftsmanship.”

Saving the Architecture of Working-Class Houses

I’ve often thought that instead of hiring ad agencies to boost the tourist economy, it might be a better investment to safeguard what tourists come to see. Specifically, we must save our ‘outdoor museums’ of older streets and houses. If one is observant about old houses and their historic exterior trim, one is likely to be shocked on revisiting a neighborhood one last saw a decade or two or three ago. In fact, up to a half of our older housing stock was still basically intact in 1970. But now, it has been remodeled almost beyond recognition.

We prize outstanding landmarks like Victoria Mansion and designate whole neighborhoods ‘historic districts.’ But on narrow side streets like Chapel, Tyng and Tate, a majority of modest working-class versions of 19th century houses have lost much of their character-defining exterior trims in quickie makeovers. And if we value our older neighborhoods as the ‘outdoor museums’ they are, then the story they tell is incomplete if only the finest houses survive, and smaller working-class houses no longer display the taste and dignity they achieved alongside their richer neighbors.

The reasons for this disparity are many, including the fact that many smaller houses may sit next to an abandoned or disorderly house in a rowdy area. And so, these get passed over by the choosier buyer.

Often the changes are done to get a better selling price, or because solutions that promise lower maintenance costs appeal to owners of rental properties. Owners may rely on the advice of builders, whose interest in pushing more product is at odds with the preservationist’s credo of ‘repair before replace.’ For an entry with a failing doorframe and leaky sidelights, a readymade replacement entry is a tempting alternative to repairing the old one, particularly if installation is done in a day. That the new entrance may not match the original, or be historically incorrect, may be of lesser concern in the face of pressing need and limited funds.

First Steps to Restore Your Trim

For greater historical accuracy, affordable repairs may be done by finding doors, windows, and trim at architectural salvage dealers instead of using brand-new replacement parts.

Portland property owners may find guidance by consulting the Maine History Network’s archive of the City’s 1924 tax assessors’ photos. For further study, find houses of comparable age and size in your neighborhood for an idea of the sorts of trims appropriate to your house. Often, clues to missing moldings and trim can be seen in their ‘ghosts’ – paint marks or clapboards jig sawed to fit around moldings – that reveal molding profiles of vanished trim.

If no comparable standard moldings can be found, some local contractors such as Paulsen Cabinet Shop in South Portland have collections of molding shaper knives ground to match a variety of moldings from local historic buildings. A company on Lincoln Street in Saco specializes in reproducing turned balusters and porch columns to order at a reasonable price.

Lasting spot repairs to partially rotted wood trim can be done with ‘The Rot Doctor,’ a patented two-part filler compound. Old-fashioned wood sash glazed with putty available from Winn Mountain Restorations will give years of service without the putty cracking. For more technical questions, consult a preservation consultant such as John Leeke of Portland.

Why It Matters

As a rule, a neat and simple contemporary design for a porch is preferable to one with imaginative but ‘conjectural’ design, or one decorated with mass-produced ‘gingerbread’ Such ornament may be fine, but it is wholly unrelated to our local historic trim styles. Replacing missing historical detail known to have existed is usually a better investment, and speaks better of one’s taste and neighborhood, than adding freakish detail of one’s own invention to the front of one’s older house.

Choose a contractor or designer who is knowledgeable and comfortable working with historical exterior trims and who has worked with Portland’s design review process.

What We Can Do To Foil the Trim Snatchers

Many neighborhoods like Providence’s Benefit Street and Worcester’s Crown Hill areas have made Block-Grant funded technical and design assistance and façade restoration grants to property owners as an integral part of multifaceted neighborhood stabilization efforts.

In Bayside, a good start would be to offer this kind of help to owners on Chestnut Street, along with compatible new infill housing on one Chestnut Street house lot that is swallowed up by a neighboring parking lot. In recent years this street, once home to Portland’s Armenian refugee community, has been unduly stressed by the Oxford Street Shelter’s homeless population. They can be seen lounging in the recessed entry of a vacant Chestnut Street house on any sunny day. It’s also the only street with intact blocks of small 19th century houses left across from Portland High School.

Restoring the columned porch and façade of the Cummings house (1846) at Chestnut Street and Cumberland Avenue would be a public art project whose symbolism and historic resonance would be a welcome rallying point for the Cumberland Avenue part of Bayside (see April 2017 WEN “Secrets of the Lost Columned Porch”).

Portland’s Historic Preservation wing of the Planning Department is woefully understaffed. Even in a Historic District, many historic properties with neglected and/or inappropriately remodeled facades can be seen not just on back alleys but on major streets like Danforth, Park and High. The volume of renovations in these boom times is such that the backlog of unresolved cases is apparently forgotten.

Portland’s Historic Preservation wing of the Planning Department is woefully understaffed. Even in a Historic District, many historic properties with neglected and/or inappropriately remodeled facades can be seen not just on back alleys but on major streets like Danforth, Park and High. The volume of renovations in these boom times is such that the backlog of unresolved cases is apparently forgotten.

In October: Restoring and Decorating with Architectural Salvage.

Tony Taylor

Tony is an architectural designer and sign artist who grew up in NYC, Hartford, and Worcester. He is a photographer and collector of architectural salvage since his teens. He has written several articles and books on urban decay and saving architectural landmarks in distressed neighborhoods.