By Adam Marletta

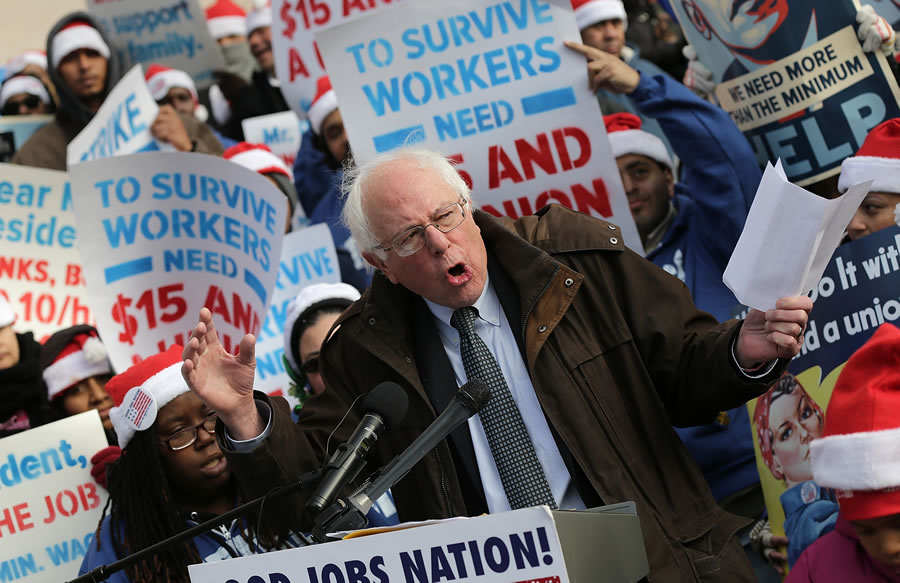

It is time to bury the pernicious myth that African Americans do not support Bernie Sanders, and that their lack of support cost him the 2016 presidential primary. Liberal, Clinton-supporting pundits constantly trotted out this baseless talking point to attack and marginalize the Vermont U.S. senator throughout his campaign. In focusing primarily on class and issues of economic justice, these commentators argued, Sanders downplayed or ignored racial concerns.

A simple Google search of “Bernie Sanders” and “black voters” illustrates the extent of this propaganda campaign.

“Bernie Sanders isn’t winning minority votes — and it’s his own fault,” lectures The Guardian’s Steven W. Thrasher (5/03/2016); “The Far Left is Still Out of Touch With Black Voters,” reads a headline in the appropriately titled, The Establishment (4/27/2017); and Politico purports to explain “Why Black Voters Don’t Feel the Bern,” (3/07/2016) — one of several snarky send-ups of the campaign’s ubiquitous tagline.

All of these articles attempt to portray the senator from lily-white Vermont as thoroughly tone-deaf to the concerns of black voters. They paint Sanders’ supporters as exclusively white and male. Indeed, Hillary Clinton’s campaign attempted — somewhat successfully, I would argue — to mount a similar smear campaign in portraying Sanders’ supporters as sexist, hyper-masculine “Bernie Bros.”

Portland Phoenix columnist and Black Girl in Maine blogger, Shay Stewart-Bouley recently revisited this theme. “During last year’s presidential primaries,” Stewart-Bouley writes in her Dec. 21, 2017 column for the Phoenix, “a lot of Black people quickly soured on Bernie Sanders.”

But this is untrue. You would never know it from liberal identitarians like Stewart-Bouley or Clinton-shills like Paul Krugman, but Sanders actually has strong support among African Americans.

For starters, Sanders is currently the most popular politician in Washington. Fifty-four percent of Americans have a favorable view of the Vermont senator, according to a Harvard-Harris poll released last August.

And that support is not limited to white voters. The poll finds Sanders’ support highest among blacks — at 73 percent. That is compared to 68 percent approval from Latinos, 62 percent among Asian Americans, and 52 percent among whites. And these results were unchanged from a similar poll from spring of 2017, which also found Sanders ranking highest (73 percent) among black voters.

Black voters are overwhelmingly attracted to Sanders’ platform of economic justice. It is no mystery why. According to Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor’s contribution to the book, The ABCs of Socialism, “By every barometer in American society — health care, education, employment, poverty — African Americans are worse off.”

Thus, 85 percent of black Americans support single-payer health care, one of Sanders’ signature campaign proposals. Same goes for black support of a $15 minimum wage. Indeed, minimum wage workers are disproportionately people of color and women.

In fact, after eight years of the country’s first African American president, blacks have lost ground in every major economic category.

And therein lies the problem in claiming Sanders “ignored race.” The accusation creates a false dichotomy between “race” and “class.”

Liberals, particularly those oriented exclusively around identity politics, are constantly trying to separate “race” and “class” into two disparate categories. According to identitarians like Stewart-Bouley, the left can either champion issues of racism (or sexism, Islamophobia, homophobia, xenophobia, etc.), or it can focus on economic inequality. It cannot, however, do both.

Clinton reinforced this false dichotomy on the campaign trail when she asked a crowd, rhetorically, “If we broke up the big banks tomorrow … would that end racism? Would that end sexism?”

Never mind, apparently, that many of the “too big to fail” banks that caused the sub-prime housing crisis that triggered the Great Recession deliberately targeted black homeowners, disingenuously selling them fraudulent refinance loans they knew the owners could not pay back.

As Stewart-Bouley writes in her column:

[Sanders] didn’t really want to talk about race. He wanted to lump it together with class. And while class and race issues have overlap and we need more meetings across those lines, the fact is that racism has its own special considerations and concerns. [Emphasis added.]

It is absolutely correct that racism and other forms of oppression have their own “special considerations.” People of color, people with disabilities, immigrants, and women (black and white) all face greater, more pervasive forms of oppression than straight white men do.

But all workers are ultimately oppressed under capitalism — an acknowledgement that is virtually absent from the reductionist lens of identity politics.

Karl Marx understood race and class to be inextricably intertwined.

“In the United States of America, every independent movement of the workers was paralyzed as long as slavery disfigured a part of the Republic,” Marx wrote in 1867 in Volume One of his three-part economic treatise, Capital. “Labor cannot emancipate itself in the white skin where in the black it is branded.”

Famed abolitionist, Frederick Douglass, arrived at similar conclusions.

“The slaveholders, in encouraging the enmity of the poor laboring white man against the blacks,” Douglass wrote, “succeeded in making the said white man almost as much of a slave as the black himself.”

“Both,” he added, “are plundered by the same plunderer.”

Sanders’ presidential campaign was not without its faults, as I have previously enumerated in this space. And it is true that Sanders needed a lot of prodding from Black Lives Matter activists to incorporate their fight against police brutality into his campaign agenda.

But perhaps his greatest contribution to the left was in clearly and unapologetically pointing to where the real levers of power in this country lie: Not with “privileged” working-class white men, but with Wall Street and the monied elites. They — not “white people” or even just “whiteness” — are the real enemies of the working class and those who struggle for racial justice.

University of Pennsylvania professor, Adolph Reed, Jr. — a prominent supporter of Sanders — dismissed criticisms that the candidate failed to connect with black voters as having “no concrete content.”

“How is it ‘economic reductionism’ to campaign on a program that seeks to unite the broad working class around concerns shared throughout the class across race, gender and other lines?” Reed countered in an Aug. 8, 2016 interview with Jacobin magazine. “Ironically, in American politics now we have a Left for which any reference to political economy can be castigated as ‘economic reductionism.’”

None of this is to suggest class is “more important” than race. Nor is it a call against workers organizing around the basis of race, gender, ethnicity, physical ability, or sexual orientation.

But even Sanders himself has acknowledged the limits of identity politics. In a widely mischaracterized, post-election speech in Boston, on Nov. 20, 2016, Sanders stated:

It goes without saying that as we fight to end all forms of discrimination, as we fight to bring more and more women into the political process, Latinos, African Americans, Native Americans — all of that is enormously important, and count me in as somebody who wants to see that happen.

…..

But … It is not good enough for someone to say, “I’m a woman! Vote for me!” No, that is not good enough. What we need is a woman who has the guts to stand up to Wall Street, to the insurance companies, to the drug companies, to the fossil fuel industry.

Let’s Bury the Myth: Black Voters ARE Feeling the Bern

By Adam Marletta

It is time to bury the pernicious myth that African Americans do not support Bernie Sanders, and that their lack of support cost him the 2016 presidential primary. Liberal, Clinton-supporting pundits constantly trotted out this baseless talking point to attack and marginalize the Vermont U.S. senator throughout his campaign. In focusing primarily on class and issues of economic justice, these commentators argued, Sanders downplayed or ignored racial concerns.

A simple Google search of “Bernie Sanders” and “black voters” illustrates the extent of this propaganda campaign.

“Bernie Sanders isn’t winning minority votes — and it’s his own fault,” lectures The Guardian’s Steven W. Thrasher (5/03/2016); “The Far Left is Still Out of Touch With Black Voters,” reads a headline in the appropriately titled, The Establishment (4/27/2017); and Politico purports to explain “Why Black Voters Don’t Feel the Bern,” (3/07/2016) — one of several snarky send-ups of the campaign’s ubiquitous tagline.

All of these articles attempt to portray the senator from lily-white Vermont as thoroughly tone-deaf to the concerns of black voters. They paint Sanders’ supporters as exclusively white and male. Indeed, Hillary Clinton’s campaign attempted — somewhat successfully, I would argue — to mount a similar smear campaign in portraying Sanders’ supporters as sexist, hyper-masculine “Bernie Bros.”

Portland Phoenix columnist and Black Girl in Maine blogger, Shay Stewart-Bouley recently revisited this theme. “During last year’s presidential primaries,” Stewart-Bouley writes in her Dec. 21, 2017 column for the Phoenix, “a lot of Black people quickly soured on Bernie Sanders.”

But this is untrue. You would never know it from liberal identitarians like Stewart-Bouley or Clinton-shills like Paul Krugman, but Sanders actually has strong support among African Americans.

For starters, Sanders is currently the most popular politician in Washington. Fifty-four percent of Americans have a favorable view of the Vermont senator, according to a Harvard-Harris poll released last August.

And that support is not limited to white voters. The poll finds Sanders’ support highest among blacks — at 73 percent. That is compared to 68 percent approval from Latinos, 62 percent among Asian Americans, and 52 percent among whites. And these results were unchanged from a similar poll from spring of 2017, which also found Sanders ranking highest (73 percent) among black voters.

Black voters are overwhelmingly attracted to Sanders’ platform of economic justice. It is no mystery why. According to Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor’s contribution to the book, The ABCs of Socialism, “By every barometer in American society — health care, education, employment, poverty — African Americans are worse off.”

Thus, 85 percent of black Americans support single-payer health care, one of Sanders’ signature campaign proposals. Same goes for black support of a $15 minimum wage. Indeed, minimum wage workers are disproportionately people of color and women.

In fact, after eight years of the country’s first African American president, blacks have lost ground in every major economic category.

And therein lies the problem in claiming Sanders “ignored race.” The accusation creates a false dichotomy between “race” and “class.”

Liberals, particularly those oriented exclusively around identity politics, are constantly trying to separate “race” and “class” into two disparate categories. According to identitarians like Stewart-Bouley, the left can either champion issues of racism (or sexism, Islamophobia, homophobia, xenophobia, etc.), or it can focus on economic inequality. It cannot, however, do both.

Clinton reinforced this false dichotomy on the campaign trail when she asked a crowd, rhetorically, “If we broke up the big banks tomorrow … would that end racism? Would that end sexism?”

Never mind, apparently, that many of the “too big to fail” banks that caused the sub-prime housing crisis that triggered the Great Recession deliberately targeted black homeowners, disingenuously selling them fraudulent refinance loans they knew the owners could not pay back.

As Stewart-Bouley writes in her column:

It is absolutely correct that racism and other forms of oppression have their own “special considerations.” People of color, people with disabilities, immigrants, and women (black and white) all face greater, more pervasive forms of oppression than straight white men do.

But all workers are ultimately oppressed under capitalism — an acknowledgement that is virtually absent from the reductionist lens of identity politics.

Karl Marx understood race and class to be inextricably intertwined.

“In the United States of America, every independent movement of the workers was paralyzed as long as slavery disfigured a part of the Republic,” Marx wrote in 1867 in Volume One of his three-part economic treatise, Capital. “Labor cannot emancipate itself in the white skin where in the black it is branded.”

Famed abolitionist, Frederick Douglass, arrived at similar conclusions.

“The slaveholders, in encouraging the enmity of the poor laboring white man against the blacks,” Douglass wrote, “succeeded in making the said white man almost as much of a slave as the black himself.”

“Both,” he added, “are plundered by the same plunderer.”

Sanders’ presidential campaign was not without its faults, as I have previously enumerated in this space. And it is true that Sanders needed a lot of prodding from Black Lives Matter activists to incorporate their fight against police brutality into his campaign agenda.

But perhaps his greatest contribution to the left was in clearly and unapologetically pointing to where the real levers of power in this country lie: Not with “privileged” working-class white men, but with Wall Street and the monied elites. They — not “white people” or even just “whiteness” — are the real enemies of the working class and those who struggle for racial justice.

University of Pennsylvania professor, Adolph Reed, Jr. — a prominent supporter of Sanders — dismissed criticisms that the candidate failed to connect with black voters as having “no concrete content.”

“How is it ‘economic reductionism’ to campaign on a program that seeks to unite the broad working class around concerns shared throughout the class across race, gender and other lines?” Reed countered in an Aug. 8, 2016 interview with Jacobin magazine. “Ironically, in American politics now we have a Left for which any reference to political economy can be castigated as ‘economic reductionism.’”

None of this is to suggest class is “more important” than race. Nor is it a call against workers organizing around the basis of race, gender, ethnicity, physical ability, or sexual orientation.

But even Sanders himself has acknowledged the limits of identity politics. In a widely mischaracterized, post-election speech in Boston, on Nov. 20, 2016, Sanders stated: