An Architectural Look at Bayside Past

Part I of Tony Taylor’s Bayside Past and Future Series

by Tony Taylor

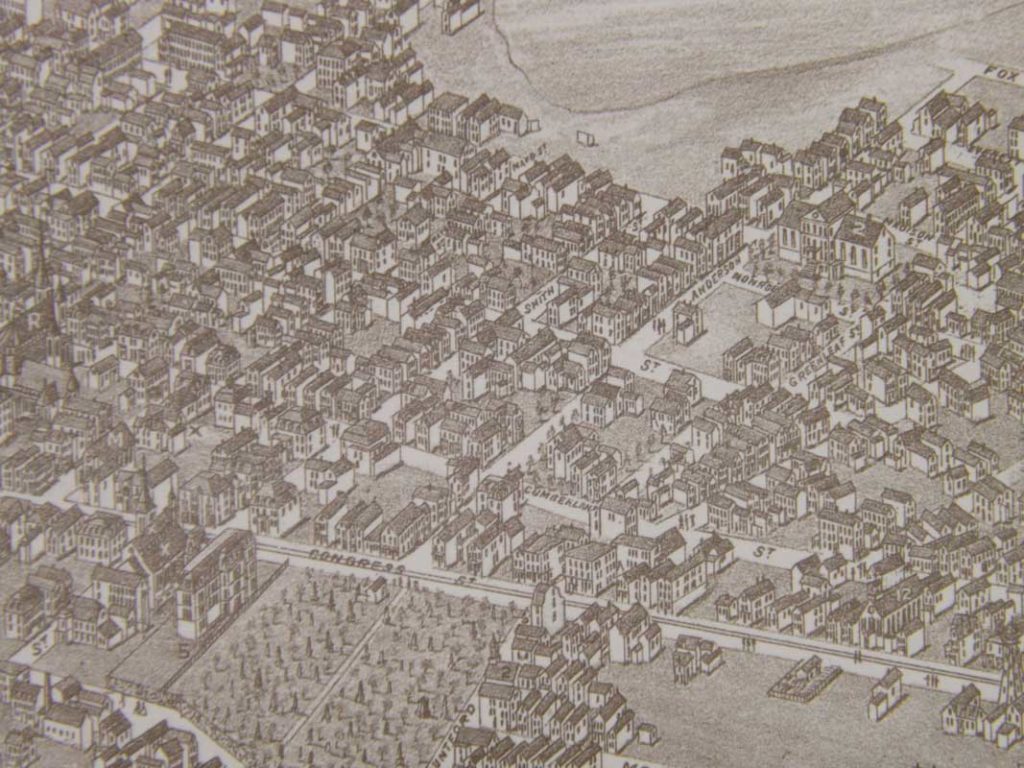

Cumberland Avenue was laid out in 1800, along with Chestnut, Cedar, Elm and Myrtle Streets, creating what we now know as the Bayside neighborhood. Cumberland Avenue joined High, State and Danforth as wider ‘monumental streets’ that were lined with larger houses of professionals and prominent merchants.

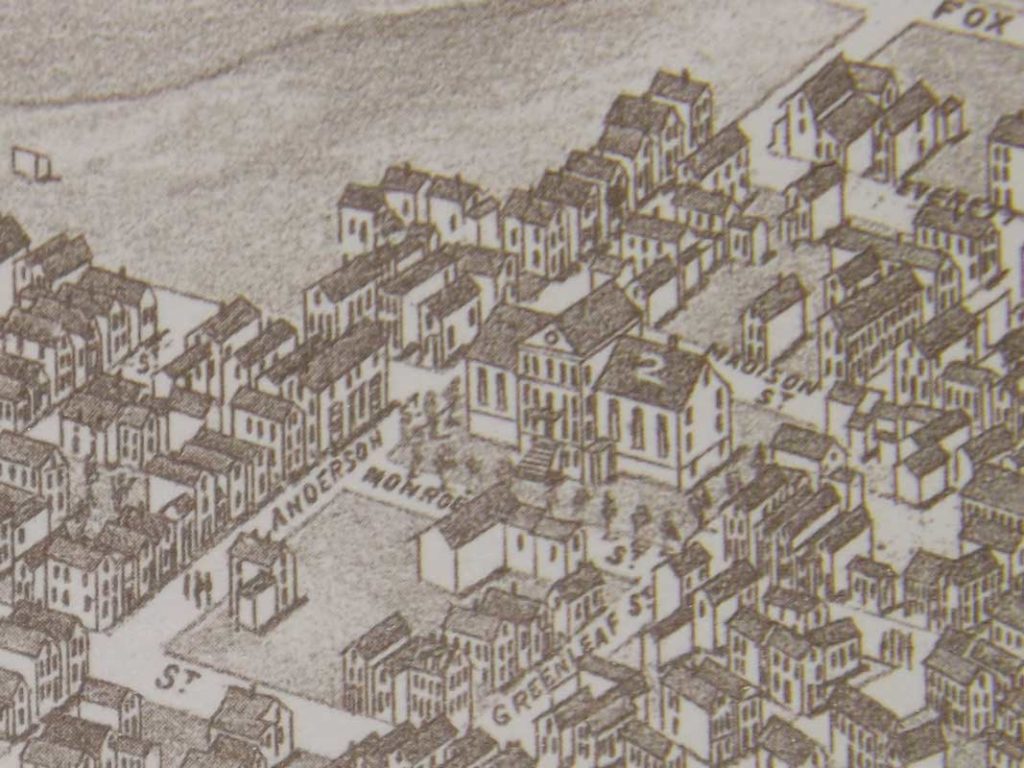

Detail of the 1875 “Bird’s Eye View” by Stoner and Warner shows East Bayside neighborhood north of Congress Street.

Mechanic Street was aptly named. It typifies the side streets branching off the north side Cumberland Avenue and sloping down towards the Back Bay. These streets were lined with more modest homes of ‘mechanics’ or skilled artisans. Many residents worked at Swasey Pottery or worked for local builders. Others found work at the Portland Stove Foundry on Kennebec Street. People of all classes were neighbors.

“Houses big and small, yes, but rich houses and poor – never,” wrote architectural historian Talbot Hamlin of the forty years before the Civil War. For the popular Greek revival style enabled houses large and small to show the same gracious architectural manners. Every house could contribute equally to civic beauty.

The Urban Cape

At first the Greek revival one and a half story Cape farmhouse – with its center doorway and a pair of windows to each side – was built on narrow city lots by simply turning it so that the narrow gable faced the street. This made the symmetrical long side a ‘garden front.’ As such, the ‘front door’ became a side entrance.

In later versions of the urban Cape, the house usually hugs the lot lines on the north or east side with a side entrance and stair hall on the cold side. This enabled the best rooms, fitted with large windows, to face the sunny side. The Cape house, with its slant-ceiling upstairs bed rooms, was economical to heat.

This house and lot pattern gives each side of a typical Bayside side street its characteristic sawtooth pattern of closely spaced front gables.

Double houses were also popular in Capes, and full two-story versions. They gave the owner another unit to sell or rent. Also, they enabled two owners to pool their resources on a grander house. Building a ‘double’ also gave each half a neighbor to help heat the twin stair halls in the middle. Some were built on raised basements, with recessed entries that partially enclosed front steps so they would fit on narrow streets.

The Great Fire of 1866

Bayside mostly escaped the Great Fire of July 4, 1866. The fire consumed much of the south side of Cumberland Avenue before jumping across to Wilmot Street. It soon burned itself out when the strong southerly wind changed direction.

The brand-new brick and granite Monroe Street Jail (1858-1866) was spared by the fire, only to be wrecked to make room for Kennedy Park a century later. Its massive granite blocks can still be seen in jumbled piles along the banks of the Presumpscot River. They were placed there, behind the city landfill near the golf course, where they were dumped in the 70’s for erosion control.

In the fire’s aftermath, the city established “Phoenix Park,” partly as a firebreak. It was later renamed Lincoln Park after the fallen President.

Major building projects rose from the ashes of the fire. These included the new Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception and the ornate stone First Baptist Church (1867). In fact, this church once stood where the Top of the Old Port parking lot is now. Unfortunately, it was torn down in the ‘90’s for office towers that were never built.

Post-Civil War

In the post-Civil War decades, some owners of 2 ½ story gabled houses converted attic spaces into an extra rental unit by raising and flattening the roof. The popular Three Decker house was the result. Often purpose-built, the Three Decker kept the traditional side hall plan, but it introduced amenities like bay windows and front and/or back porches. The porches brought private spaces partly out into the public realm of the street.

Some builders experimented with higher residential densities to meet the demands of a growing city. The double three-decker or ‘6-tenement’ combines two adjoining Three Deckers with two apartments per floor that share a central hall. Some cheaper Three Deckers housed ‘front’ and ‘back’ apartments on each floor with minimal yard space. Some even stretched over back-to-back lots and had ‘fronts’ on two streets.

Indeed, the once scorned Three Decker is now recognized as a classic New England form of urban working class housing. Contemporary versions are making a comeback. They are found in modified form today as infill housing in older neighborhoods like Bayside.

Ultimately, the larger of the old tenements show the inability of 19th century design and technologies to provide safe and attractive affordable housing at higher densities. The best of today’s creative contemporary architects who work in Bayside have accepted the challenge.

The Series Continues…

Tony Taylor’s four-part series explores the architectural and social history of the Bayside neighborhood. “Postwar Blues” arrives with the June issue. The Great Depression and WWII led to deferred maintenance, urban blight, and poor living conditions in Bayside. The Portland Renewal Authority was cofounded in 1950 to address those conditions. The City seized buildings by eminent domain for “Renewal Project 1” on the south side of Cumberland Avenue between Oak and Casco Streets. The project never happened. Major accomplishments of the era included Munjoy South and Kennedy Park housing developments, and the building of the Franklin Arterial.

And in July…

Tony looks at a few of the many Bayside planning studies done from the 60’s to now, in “Bayside of the Mid-Century Remembered.” Consider how and why some of the consultants’ ideas were adopted, and some not. How did the continuity of Cumberland Avenue come to be so disrupted by blank windowless facades, surface parking, and parking garages? And how was Bayside’s role defined and shaped by the districting, zoning and planning practices and priorities of the 60’s, 70’s, 80’s and 90’s?

In August…

August’s Bayside focus features my walking tour of Oxford Street. A police cruiser parked all day at the Cedar Street corner points to the impact of the concentration of homeless shelters. And a talk with longtime resident and activist Jay York, who lives near where Oxford Street is dead-ended by the Franklin Street, will explore the history of the first homeless shelter in Bayside. Also, Jay cites benefits to the neighborhood of keeping Oxford Street a dead-end. We’ll also look at the new Bayside Anchor affordable housing by Kaplan-Thompson Architects of Portland.

Finally, in September…

In September’s issue we’ll look at some tentative conclusions and suggestions based on how past planning and development ideas have panned out in Bayside. What can be learned from the best and worst of what’s happened here in recent decades? In conclusion, we’ll look at two small side streets off Cumberland Avenue, how they came to be overshadowed by larger events in the surrounding area, and what revitalization strategies could turn their blight into neighborhood inspiration.

Tony Taylor

Tony is an architectural designer and sign artist who grew up in NYC, Hartford, and Worcester. A photographer and collector of architectural salvage since his teens, Tony became concerned about urban decay and became an advocate for saving architectural landmarks in distressed neighborhoods. He has written several articles and books on related topics.