Bayside’s Postwar Blues

by Tony Taylor

“There’s been a widespread perception around here that Bayside was simply ignored architecturally because it was working class. For a lot of the time it didn’t hit the radar,” observed Steve Hirshon of the East Bayside Neighborhood Organization, founded in 2007.

I’d come to the Cumberland Avenue storefront housing the former 3 Fish Gallery to review exhibit materials from the 2003 “Best Laid Plans.” The exhibit chronicled the history of planning efforts in Bayside in the 50’s and 60’s, and interestingly I thought, neighborhood folks’ reactions to what the planners proposed.

The 1965 Annual Report of the Portland Renewal Authority saw the agency’s mission this way:

You will recall that renewal planning was initiated during a period of self-examination of our city at the end of WWII after the combined effects of limited repairs during the depression years, and heavy use combined with inadequate repairs during the war years became apparent…. Dilapidation was spreading with increasing rapidity…. It was found that our needs included (1) areas requiring total clearance for re-development, (2) rehabilitation of existing structures, and (3) prevention and conservation to halt the spread of blight.

The Authority saw its mission as the physical rejuvenation and economic strengthening of the downtown core. Towards that end, the downtown core was thought of as a series of largish districts, each with its character and function. The southwest quadrant, starting with the Park Street area, was recognized as a stable area suitable for Historic District protections. Meanwhile Bayside, extending north from the downtown part of Cumberland Avenue, was designated a “regrowth area” appropriate for a mix of new high rise housing and parking for the Congress Street shopping area.

Downtown Project #1

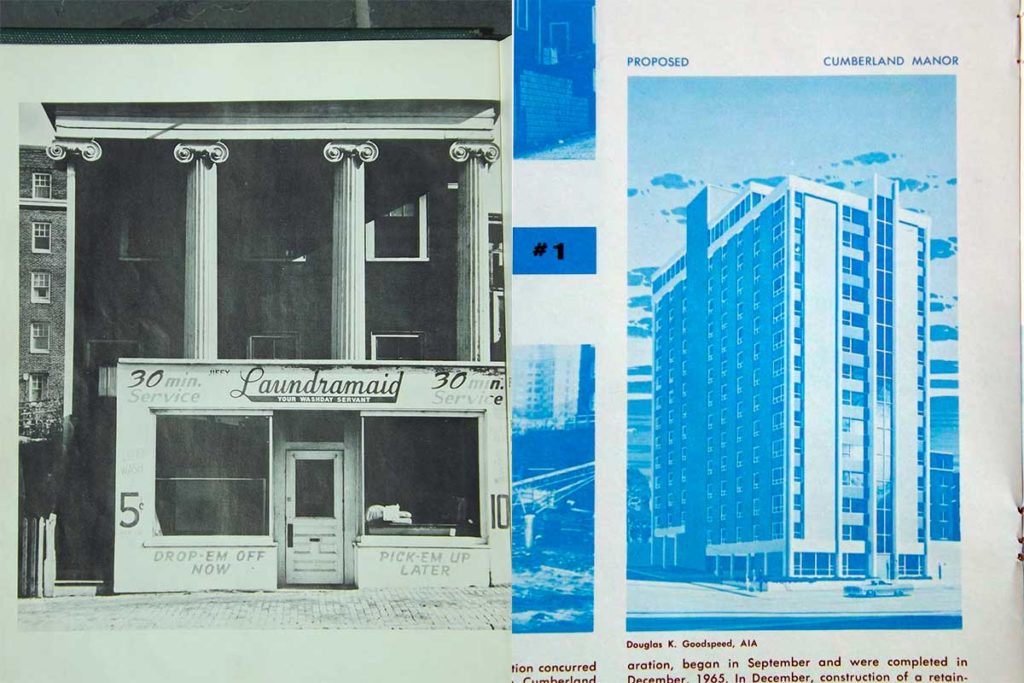

Using eminent domain, the Portland Renewal Authority acquired a block bounded by Shepley, Oak and Casco Streets and Cumberland Avenue in 1961 to provide surface parking convenient to the central business district. In 1965 the Urban Renewal Administration sold this “Downtown Project #1” site to “Cumberland Manor,” a nonprofit intending to build a fifteen-story apartment tower for the elderly that wasn’t built there, but whose impulse was to be realized across the street two decades later as the Back Bay Tower. Instead, the telephone company built a windowless “riot renaissance” style concrete block on the corner of Oak Street and Cumberland Avenue, site of a distinguished Greek revival house lost to “Downtown Project #1.” MECA later renovated the telephone building for classrooms.

“Before” and “After” pictures of “Downtown Project #1” from the 1965 Portland Renewal Authority annual report. The apartment tower was never built.

Also in 1965 the Renewal Authority and the Chamber of Commerce commissioned a two-year downtown planning study, “Patterns for Progres,s” from internationally renowned Victor Gruen Associates. Founder Victor Gruen received his architectural training in Vienna, and later moved to the US to escape the Nazis. Gruen’s firm specialized in designing shopping centers as well as developing revitalization plans for sagging downtown retail areas in many American cities.

A focus of “Patterns for Progress” was to look at how to improve downtown parking and traffic circulation to connect the retail and office core with I-295. For the threat of competition from suburban shopping malls was widely understood in the 60’s, even as downtown Portland boasted a Sears, the Porteous flagship store, specialty clothing shops like the Rines and Payless Shoe stores, W.T. Grant and Kresge’s department stores, several first run theaters, and specialty shops like the pop music haven Recordland.

As envisioned by “Patterns for Progress,” the new Franklin Arterial limited access connector would link I-295 to a downtown traffic loop around Congress Street. The plan was to widen Spring Street and Cumberland Avenue into high-volume streets interconnecting with Franklin Arterial, and to make High and State Streets one-way. The Spring Street boulevard concept got no further than High Street, for Greater Portland Landmarks rallied to save the Park Street neighborhood from the demolition required by road widening plans.

“Patterns for Progress” also envisioned three downtown areas developed for high density housing. The Lincoln Park Housing concept envisioned clearance for multifamily housing clustered around the First Baptist Church – a mix of high- and low-rise buildings with the low-rise ones along Congress Street facing Lincoln Park. Downtown Project #1 was to be the nucleus of high-rise housing along a widened Cumberland Avenue. The stable and historically significant neighborhood south and west of Park Street was earmarked for rehabilitation and preservation of existing structures.

Restorative Justice

Despite such last-ditch efforts, Congress Street was soon to see the collapse of the department store economy in the 80’s and its subsequent rebirth as an arts district. Conceptual plans like those of “Patterns for Progress” that saw Portland’s downtown in terms of various districts with different functions contributing to a healthy downtown retail and service economy also had unintended and lasting consequences. What if the Civic Center had been built on a site between High and State Streets across from the Eastland Hotel? Several intact blocks of Victorian townhouses would have been obliterated. That was another of the “Patterns for Progress” study’s ideas.

Targeting the relatively stable West End for rehabilitation and Historic District protections made sense, but resulted in lack of city oversight over private housing rehabs in other downtown neighborhoods like Bayside. Mounting losses of historic character along Cumberland Avenue and in Bayside was the unintended consequence.

The Downtown Project #1 fiasco and the abandonment of the Lincoln Park neighborhood concept, as envisioned by “Patterns for Progress” with the demolition of the First Baptist Church, left the downtown part of Cumberland Avenue scarred with surface parking in once-promising areas. For without a historic preservation ordinance, the City could do nothing to prevent the loss of the historic 1867 church across the park.

‘Restorative justice for neighborhoods’ is simply the idea that neighborhood renewal can be informed with insights into an area’s historical vicissitudes in recent decades. Its time has come for Bayside.

The Series Continues…

Tony Taylor’s four-part series explores the architectural and social history of the Bayside neighborhood. “Ghosts of Bayside” looks at the architecture common to the neighborhood in the late 1800’s. The neighborhood’s survival of the Great Fire and post-Civil War period are explored.

Tony looks at a few of the many Bayside planning studies done from the 60’s to now, in “Bayside of the Mid-Century Remembered.” Consider how and why some of the consultants’ ideas were adopted, and some not. How did the continuity of Cumberland Avenue come to be so disrupted by blank windowless facades, surface parking, and parking garages? And how was Bayside’s role defined and shaped by the districting, zoning and planning practices and priorities of the 60’s, 70’s, 80’s and 90’s?

In August…

August’s Bayside focus features Tony’s walking tour of Oxford Street. A police cruiser parked all day at the Cedar Street corner points to the impact of the concentration of homeless shelters. And a talk with longtime resident and activist Jay York, who lives near where Oxford Street is dead-ended by the Franklin Street, will explore the history of the first homeless shelter in Bayside. Also, Jay cites benefits to the neighborhood of keeping Oxford Street a dead-end. We’ll also look at the new Bayside Anchor affordable housing by Kaplan-Thompson Architects of Portland.

Finally, in September…

In September’s issue we’ll look at some tentative conclusions and suggestions based on how past planning and development ideas have panned out in Bayside. What can be learned from the best and worst of what’s happened here in recent decades? In conclusion, we’ll look at two small side streets off Cumberland Avenue, how they came to be overshadowed by larger events in the surrounding area, and what revitalization strategies could turn their blight into neighborhood inspiration.

Tony Taylor

Tony is an architectural designer concerned about urban decay in distressed neighborhoods.