By Harlan Baker

“I’ve been here all my life,” said Nance Parker, director of The Shoestring Theater. “All My Life” is also the name of one of the shows that gained the most publicity for the theater. It was based on the lives of the working class women who lived in Portland’s West End. The theater and Parker have been a fixture in the West End for forty years. The theater’s workshop on the third floor of the old Brackett Street Dress factory is covered with masks, giant puppet heads, marionettes, flyers, and posters for Shoestring shows and parades.

The theatrical ancestor for the Shoestring Theater was The Blackbird Theater, founded by Andy and Amy Trompettor. They came to Portland to co-direct the Children’s Theater of Portland. The Children’s Theater was housed in the Woodfords Corner Fire Barn. The Fire Barn was also the home of The Blackbird Theater.

Nance Parker was a performer with the Children’s Theater. Watching a performance of Blackbird’s “Rat Story” she was intrigued. “Actors were wearing giant rat head puppets,” she said. “Everyone else hated the show. But something in that struck me.”

Trompettors Start the Blackbird Theater

Andy Trompettor, a Holocaust survivor, and Amy met each other working with Bread and Puppet Theater in New York. They soon married.

The theater attracted the attention of Portland’s counterculture and was receiving favorable attention from the local media.

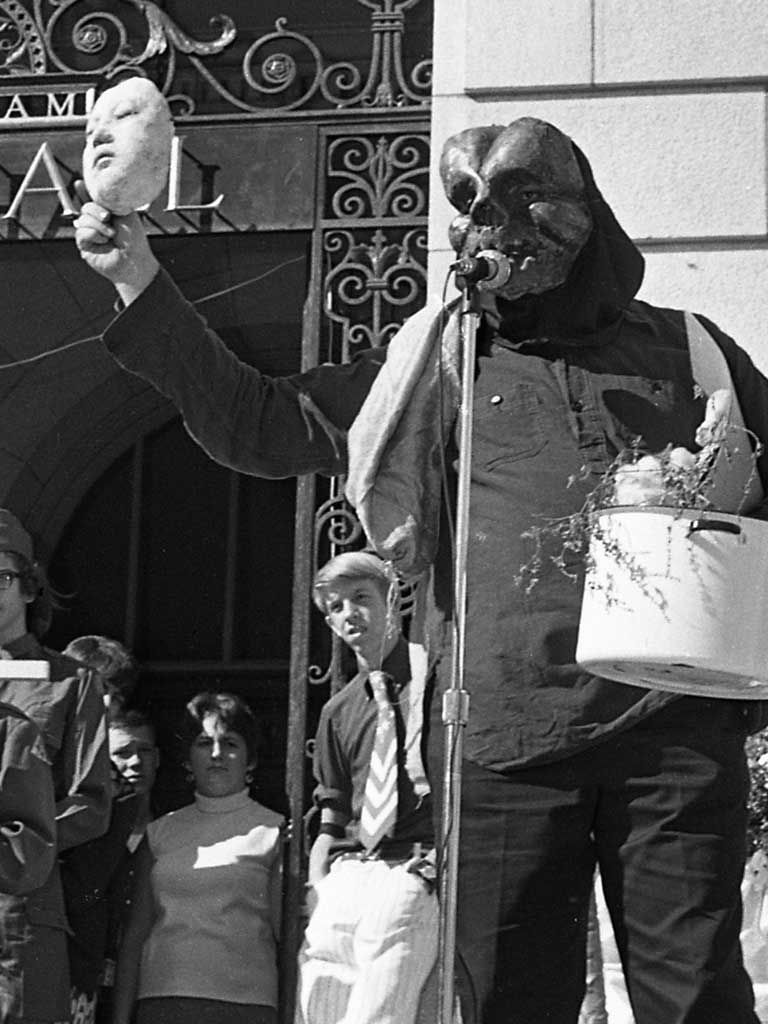

The productions relied mostly on movement, sound, and music with minimal dialogue, often just narration. A jug band provided musical accompaniment. Actors would often perform in masks with very simple pieces of clothing. Scenery was minimal. Large and small puppets filled in for the lack of scenery.

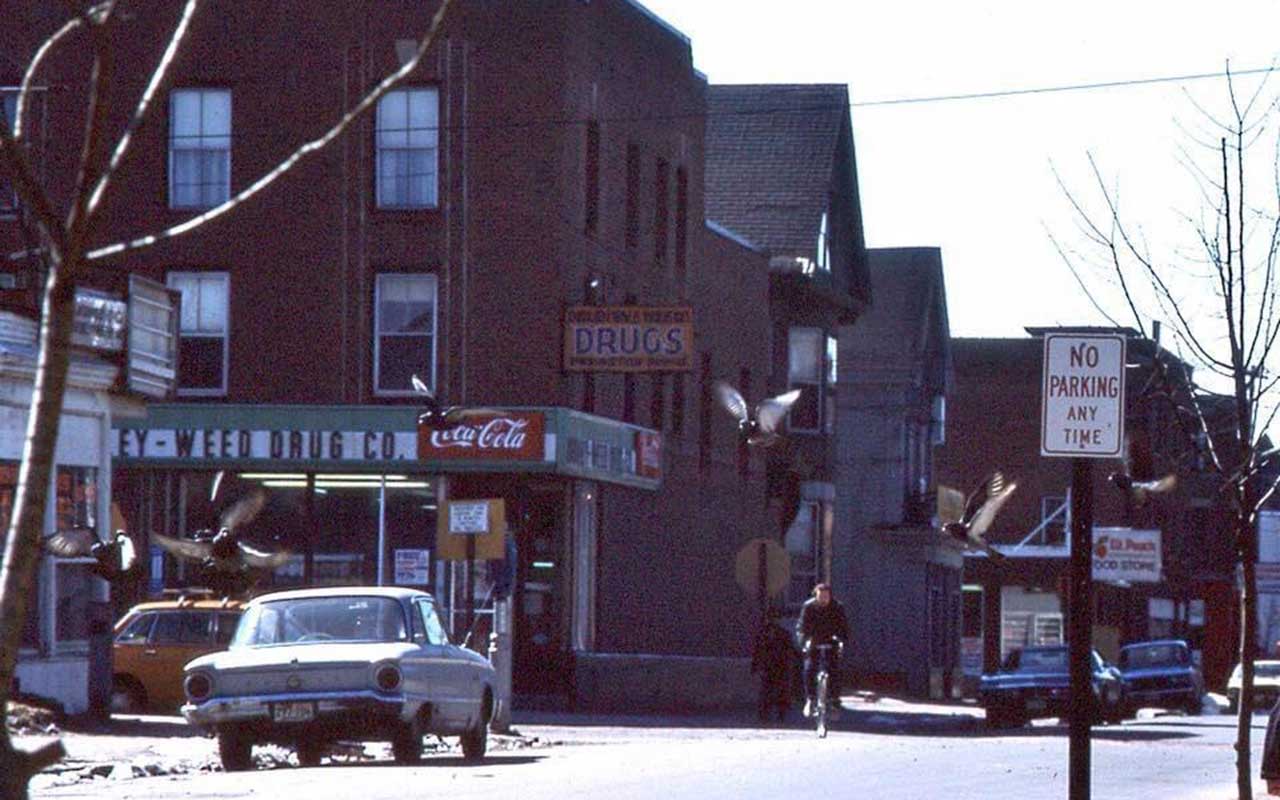

-Photo courtesy of Portland Public Library Special Collections

It was open to anyone who wanted to participate and recruited people on the spot. A person attending a production or rehearsal might also find themselves assigned a role in the show.

“We need someone to wear a mask…”

West End activist Pierre Shevenall was recruited on the day of the nationwide anti-Vietnam war moratorium on October 15th, 1969.

He was walking up High Street and noticed an assembly of people dressed in black with large paper mache puppets in front of the Eastland Hotel. Someone called out to him, “We need someone to wear a mask and a black garment and walk down Congress Street.”

Shevenell joined the procession. “I was walking on the sidewalk”, he said, “and I see my cousin and two banker friends. They tried hard not to look at this strange thing. I didn’t know what it was all about, but I thought hey I like this”.

At the end of the rally the theater performed, “A Mother Says Goodbye to Her Son,” an anti-war morality play. Actors wearing masks and black clothing mimed the action described by a narrator.

I attended a rehearsal one night at the invitation of Pierre Shevenell. Andy Trompettor saw me sitting in the front row. He walked over to me and asked me to step into the playing area. Suddenly I was thrust into the action of the play.

The Trompetters left Portland for a tour across the United States. When they returned to Maine they were based in Rangeley, Maine. They continued to present shows and toured the county fair circuit with Punch and Judy.

They toured internationally. It was during a tour in France that their marriage ended, which resulted in the end of the Blackbird Theater.

Rebirth as The Shoestring Theater

Sometime after returning from France, Pierre Shevenell and company member Michael Romanyshyn were conversing over a few beers at a bar on Danforth Street about reviving the theater. “We wanted to continue the tradition of political theater based in the neighborhoods,” said Shevenell.

The theater became known as The Shoestring Theater. Shevenell and Romanyshyn performed puppet shows and a “Cranky movie,” at any location they could find. More people joined the company.

A growing company needed a permanent home. Romanyshyn and Shevenell approached the board of Youth in Action, a neighborhood youth group located in the old dress factory on Brackett Street, known as the “People’s Building.” The third floor of the building became a workshop for the theatre. The theater performed all over Maine and opened the Old Port Festival with a parade lead by giant puppets.

Where she learned to stilt walk.

Elizabeth Whitman recalls her experience with the theater in the mid-1970s. She was put to work right away making puppets. “The initiation”, she said, “was just getting up that fire escape.” It was also where she learned to stilt walk.

She became one of the core members of the theater. “I don’t really remember any official director, as in anyone having any final decisions. People came up with an idea for a show and interested people supported it,” she said. According to Whitman, Amy Trompetter kept a relationship with the theater by making several visits to run workshops and work on various projects.

An 18-year-old Nance Parker joined the Shoestring Theater in the late ’70’s after working with the Profile Theater, now Portland Stage, as a paid stage manager. She left to work in Germany but returned in 1982 to become Shoestring’s director. For the past forty years she has been carrying on the tradition of this iconic theater. One she has known and valued for the past fifty years.

Epilogue

Andy Trompetter died in 1979 at age 37. Amy Trompetter founded the Redwing Blackbird Theater in upstate New York.

Harlan Baker is currently writing a book on Portland Theater in the 1970s, 80s, and 90s. This is a condensed version of one of the chapters.