The Plight of Millennials

by Luke deNatale and Tony Zeli

No one ever said it was easy being young. People in their twenties and early thirties are likely to struggle economically. Millennials are saddled with college debt, if they are lucky enough to have attended. And they find few prospects for high paying jobs. Put the two together and it is hard to expect any young person to build savings for the future.

Maybe struggle is a part of growing up. But, can the places where millennials choose to live determine how well they fare economically? And if so, what should Maine and Portland be doing to help our younger generations? Below we look at the issues that millennials themselves list as their biggest concerns. And next month, the West End News will examine ways the city and state can address those concerns.

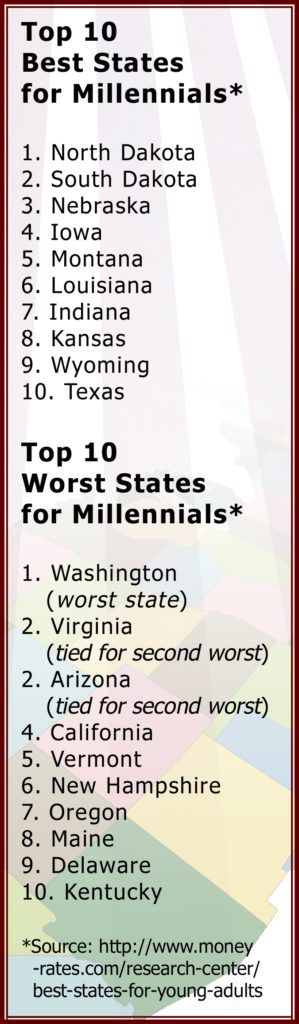

Maine Ranks Among Worst States for Young People

The website Moneyrates.com ranks Maine eighth out of ten worst states for millennials. The savings and loan rate aggregator bases the rating on Maine’s lack of “youthfulness, rental availability and access to high-speed broadband.”

The website Moneyrates.com ranks Maine eighth out of ten worst states for millennials. The savings and loan rate aggregator bases the rating on Maine’s lack of “youthfulness, rental availability and access to high-speed broadband.”

District Two School Board Representative Holly Seeliger is a millennial. She grew up in rural New England and graduated from USM. She is not surprised to hear that Maine might not be the best place for young people to choose to live.

“I think this state is notoriously bad to young people. That is just the way it’s always been… as long as I’ve been paying attention. When I graduated from high school my friends quickly left the state to go to out-of-state colleges or find work elsewhere,” says Holly Seeliger.

What draws them away? According to Holly, “It’s cheaper housing, easier jobs, better public transportation … internet. Just accessibility to basic life needs.”

Portland v. Maine

Portland is one of the youngest cities in Maine. Per the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey for 2015, ages 20 to 34 make up 29.2% of Portland’s population. Compare that to Maine as a whole, where ages 20 to 34 make up only 17.3% of the population.

As such, Portland is more “youthful” than the rest of the state. Also, Portland offers greater access to infrastructure like broadband and greater access to jobs.

Emily Young is a millennial who works as a server at a local restaurant and as an adjunct professor at a local college. She explains that it seems fairly easy to find employment in Portland. However, it’s certainly a different story for other parts of the state.

“From my own experience, I attempted to get a job in Farmington after college, it was so hard to get a job. There are not that many job prospects there. You may be able to find work part-time in college, but actually trying to live there and have a job was really tough. It was the longest time that I was jobless.”

In September of last year, Downeast magazine published an article by Ron Currie Jr. documenting the plight of a local high school graduate in Millinocket. The graduate struggled with few prospects in a town wracked by mill closures. It serves as a relative contrast to Portland, which is generally known for its economic vibrancy in comparison with the rest of the state.

But, while some aspects of Moneyrate.com’s criteria apply better to central and northern parts of the state, millennials in Portland may agree with the website on the dearth of rental availability.

Housing

In this category, Maine places among the lowest ranking states for millennials to live in. All the millennials we interviewed acknowledge that the housing capacity in Portland is near maximum. But they admit that they are very fortunate to have decent housing with conscientious landlords. They all agree this is fairly rare in a popular, youthful city where many people struggle to find quality housing.

Andrew Thompson is a millennial working in Portland. He currently works as an admissions coordinator for a local college and as a bartender for a local grill.

Thompson provides an anecdotal story.

“A previous employer I worked for was looking for a multi-unit home. They kept running into a similar issue where they’d locate a house within their price range. In their words, they’d be ‘undercut’ by someone coming in from out of state willing to pay $500,000 or $600,000 in cash to start an investment property.”

Gentrification

The attractiveness of Portland as a small New England city certainly has increased our popularity to people “from away.” It seems logical that gentrification follows.

Emily Young remarks that Portland has changed drastically from when she initially moved to the city.

“Aside from housing being more expensive, downtown businesses have changed to be more based towards affluent people. I’m disappointed that Paul’s grocery store is gone. I feel like we needed a cheap grocery downtown and now we have a huge antique store in its place. People that hangout and live on that block do not buy antiques,” says Young.

Holly Seeliger makes a similar observation, “Now places where people used to buy food like grocery stores, like Paul’s – It’s hard to find where you can buy toilet paper and soap in town now without having a car or taking the bus. So, little things all add up to [a lack of] walkability and livability.”

Living Wage

Admissions coordinator and bartender Andrew Thompson says a livable minimum wage is his top concern.

“I think a lot of us work in the restaurant-service industry and making sure that there is a way out of these jobs or a growth in support for the minimum wage. Getting everyone to a decent living wage should be the goal.”

School Board Member Holly Seeliger notes, “Most of the jobs we encounter are tourism or service related. Or in my case, nonprofit. Which are all notoriously low paying. So, I think the options for Maine workers revolves around traditionally low paying jobs.”

She continues, “I don’t think they have to be low paying. I think that’s a choice that we’ve made. So maybe we should think about not just bringing in other types of jobs that pay well, but also raising the wages for the workers that we already have here, who are running the city.”

Adjunct professor and server Emily Young concurs on this point, “I think raising the minimum wage to be a livable wage is kind of a no-brainer.”

The city of Portland passed an ordinance in September 2015 increasing the minimum wage to $10.10 effective January 1st, 2016. In 2017 the wage increases to $10.68 an hour. And hereafter it will be tied to inflation as measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI).

Regarding the price of labor in general, Andrew Thompson believes that there should always be the willingness to discuss what someone’s time is worth.

“I would like for there to be an attitude shift in the way that work is valued. What is someone’s time actually worth? I think we should be able to have an open dialogue on the subject,” he says.

Job Mobility

An often-cited motif of millennials is that they switch jobs frequently. This assertion is accurate. In fact, within the last twenty years the number of companies an individual has worked for within a five year span has doubled, according an article by LinkedIn, an employment-oriented social media site.

This is something that Emily Young recognizes as completely different from prior generations.

“The economic climate is so different from when our parents and grandparents were living it. I don’t feel like I could wish for the job security that they had. I don’t even know what that would look like these days,” she says.

Why It Matters

What happens when millennials cannot make ends meet?

“They end up moving back in with their parents,” says Holly Seeliger.

So, baby boomers beware. The plight of the millennials is your plight too.

Of course, struggling millennials may also opt to move out of state. Although the good news is that moving away is not always their first option.

For Holly Seeliger, Maine has too much to offer to leave the state behind.

“And so, I’ve made a conscious decision to stay in this state because I love my state. I love living here and that we still have clean air and water and all that sort of stuff. I’m not really into the huge megacities that a lot of my friends have had to move to,” she says.

As such, there is hope that some millennials will choose quality of life and stay in Maine. Of course, even if they stay, there is a third option for struggling millennials.

“They try to look for places in some of these other smaller cities such as Biddeford, Westbrook, even Lewiston-Auburn and Bangor,” notes Holly.

Portland cannot afford to lose young renters and homeowners to bedroom communities. We need their culture, energy and talent if we wish to be a successful city. In the February issue, we will explore some of the options the city and state have. We must attract and keep young talent here.

Overall, Moneyrates.com was aggregating factors in Maine as a whole when they placed Maine towards the bottom of the worst states for millennials. Luckily, at a hypo-local level in Portland it is a different story.

Still, high rent is a factor for many, and millennials are looking for upward mobility, livable wages and less gentrification. To put it another way, we want affordable groceries. Not antiques.

Editor’s Note

Since our interview, Holly Seeliger’s position at a local nonprofit was eliminated. She is currently seeking new employment.

Continue to part two of the series, “Millennials and Wages.”