By Adam Marletta

Portland is becoming as expensive to live in — and potentially as “bougie” — as my hometown of Kennebunk. From 2014 – 2016 my mother rented a small house in Kennebunkport for over $1,500 a month. That is about what you would pay for a one-bedroom apartment in Portland. If gentrification and rapid development trends continue in Portland, the city will soon become the next Kennebunkport, Ogunquit, or Cape Elizabeth—three of the wealthiest towns in Maine.

During our time at 171 Wildes District Road (I was living with my mother at the time; yay for being part of “generation screwed,”), we endured an infestation of hornets, a broken toilet which my mother was forced to pay to fix herself, and the eerie noise of some critter scampering around in the scaffolding of the ceiling at night.

The landlord’s default solution to all of these problems was to attempt to fix them herself, rather than call an exterminator, a plumber or pest control. Problem was, she was not at all qualified to deal with any of these issues. She was just too cheap to call a professional.

The hornet infestation threatened to make the house uninhabitable. And the landlord never addressed the critter noise at all. Whatever was breeding and wreaking havoc up in the scaffolding was still doing so when we left the house.

When we moved out, the landlord demanded my mom have the place professionally cleaned — and that she pay for it herself. Every apartment I have ever lived in required little more than a thorough broom-sweeping upon moving out. Any additional cleaning was the responsibility of the property owner.

Countless Portland residents have similar landlord “horror stories.” These stories reflect the plight of working-class Portlanders to find and maintain decent housing in a city that is becoming increasingly unaffordable.

Nationally, 11 million Americans spend at least half of their income on rent.

The Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram, in an in-depth series on the city’s housing crisis in 2015, found that rents in Portland have increased 40 percent in the last five years, alone. This trend, combined with stagnant wages and city leaders’ obsession with chasing down luxury condo deals with corporate developers, is forcing working-class residents out of the city.

“Question 1” on the Portland Nov. 7 ballot, could change that. If passed it would curb some of the ability of landlords to arbitrarily raise rents and evict tenants. The referendum is by no means a panacea for housing rights in Portland. But it would offer much needed relief for working-class residents struggling just to stay in their homes.

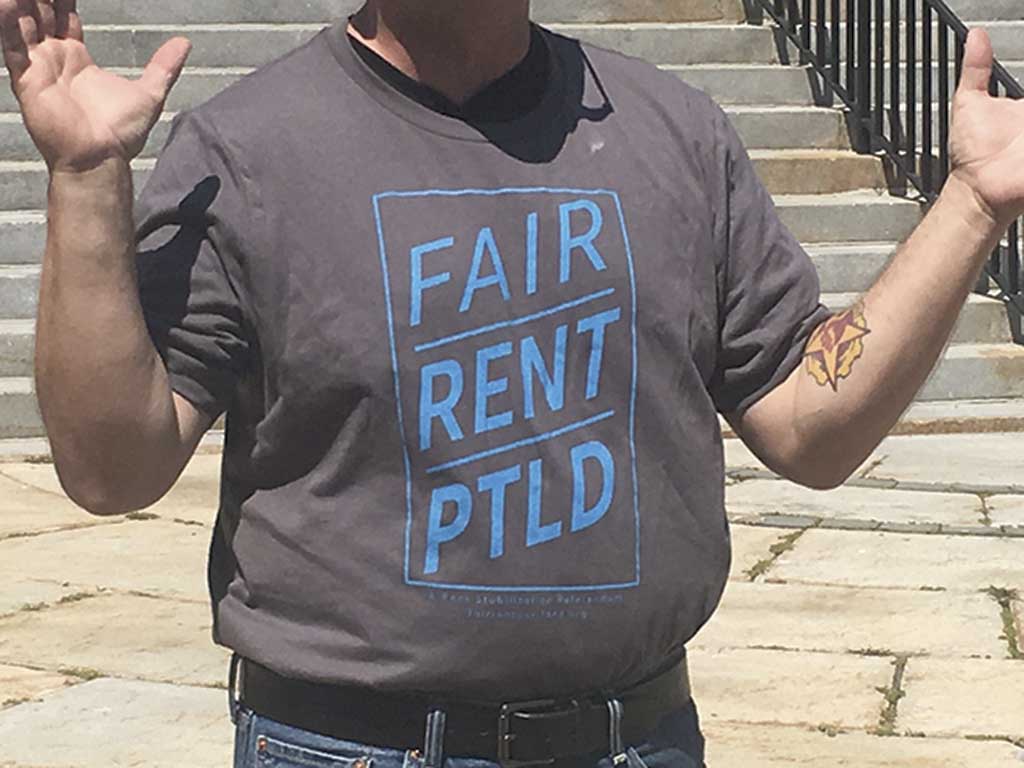

But the measure, spearheaded by the citizen-led group, Fair Rent Portland, is up against some fierce opposition.

A bourgeois coalition of landlords, business interests, and the arch-enemy of the working class, the Portland Regional Chamber of Commerce, is intent on crushing the referendum. And the opposition, operating under the name, “Say No to Rent Control,” has vastly outraised the referendum’s proponents. Say No to Rent Control has about $100,000 in campaign contributions (much of it from corporate and out-of-state interests), compared to Fair Rent Portland’s $3,200.

The fact that this is an odd-year, non-presidential election also does not bode well for the rent-stabilization effort. Voter turnout is likely to be low —though Fair Rent could benefit from the statewide “Question 2,” which concerns Medicare expansion, and is likely to be a major draw for voters this year.

Indeed, housing, like health care, should be a human right. But contrary to ruling-class ideology, homelessness is not a result of a lack of housing. A simple drive through Lewiston-Auburn reveals the dearth of empty, former mill buildings, just rotting away, unused. These buildings could easily be restored into housing for the poor and homeless.

But landlords and proptery developers are not in the business of providing homes to people who need one. They are in the business of making money. Sure, landlords often claim they have “no control” over how much they charge for rent — that such costs are determined by The Market. But this is nonsense. Landlords are business people — part of what Marx and Engels called the “petit bourgeois,” or “small bourgeois.” Like any capitalist, their aim is to make a profit.

Thus, homelessness exists in society for the simple fact that it is not profitable to rent to those with no money. And do not get me started on the cruel joke that is “affordable housing” — which is frequently unaffordable and substandard. Little wonder then, that the major affordable housing companies–Avesta Housing, Shalom House–have come out against Question 1. Like the misleadingly termed “nonprofit” sector, affordable housing exists to make a profit. It has nothing to do with providing housing for those who cannot afford it.

The anarchist collective, CrimethInc. is correct: We don’t have to live this way. Portland should not be the exclusive province of the wealthy and telecommuters “from away.” Working-class residents need to take our city back. If passed, Question 1 would be a significant gain for the working class.

As Owen Hill writes in a Feb. 25, 2016 story for the International Socialist Organization’s monthly newspaper, Socialist Worker, the left must fight “not just against what is wrong, but for our own vision of what is right.”

“[A]n organization fighting against gentrification and evictions cannot simply move from attempting to stop one eviction to attempting to stop the next,” Hill writes. “It has to also project a bigger vision of what housing justice looks like.”

Evict the Landlord! Vote “Yes” on Rent Control

By Adam Marletta

Portland is becoming as expensive to live in — and potentially as “bougie” — as my hometown of Kennebunk. From 2014 – 2016 my mother rented a small house in Kennebunkport for over $1,500 a month. That is about what you would pay for a one-bedroom apartment in Portland. If gentrification and rapid development trends continue in Portland, the city will soon become the next Kennebunkport, Ogunquit, or Cape Elizabeth—three of the wealthiest towns in Maine.

During our time at 171 Wildes District Road (I was living with my mother at the time; yay for being part of “generation screwed,”), we endured an infestation of hornets, a broken toilet which my mother was forced to pay to fix herself, and the eerie noise of some critter scampering around in the scaffolding of the ceiling at night.

The landlord’s default solution to all of these problems was to attempt to fix them herself, rather than call an exterminator, a plumber or pest control. Problem was, she was not at all qualified to deal with any of these issues. She was just too cheap to call a professional.

The hornet infestation threatened to make the house uninhabitable. And the landlord never addressed the critter noise at all. Whatever was breeding and wreaking havoc up in the scaffolding was still doing so when we left the house.

When we moved out, the landlord demanded my mom have the place professionally cleaned — and that she pay for it herself. Every apartment I have ever lived in required little more than a thorough broom-sweeping upon moving out. Any additional cleaning was the responsibility of the property owner.

Countless Portland residents have similar landlord “horror stories.” These stories reflect the plight of working-class Portlanders to find and maintain decent housing in a city that is becoming increasingly unaffordable.

Nationally, 11 million Americans spend at least half of their income on rent.

The Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram, in an in-depth series on the city’s housing crisis in 2015, found that rents in Portland have increased 40 percent in the last five years, alone. This trend, combined with stagnant wages and city leaders’ obsession with chasing down luxury condo deals with corporate developers, is forcing working-class residents out of the city.

“Question 1” on the Portland Nov. 7 ballot, could change that. If passed it would curb some of the ability of landlords to arbitrarily raise rents and evict tenants. The referendum is by no means a panacea for housing rights in Portland. But it would offer much needed relief for working-class residents struggling just to stay in their homes.

But the measure, spearheaded by the citizen-led group, Fair Rent Portland, is up against some fierce opposition.

A bourgeois coalition of landlords, business interests, and the arch-enemy of the working class, the Portland Regional Chamber of Commerce, is intent on crushing the referendum. And the opposition, operating under the name, “Say No to Rent Control,” has vastly outraised the referendum’s proponents. Say No to Rent Control has about $100,000 in campaign contributions (much of it from corporate and out-of-state interests), compared to Fair Rent Portland’s $3,200.

The fact that this is an odd-year, non-presidential election also does not bode well for the rent-stabilization effort. Voter turnout is likely to be low —though Fair Rent could benefit from the statewide “Question 2,” which concerns Medicare expansion, and is likely to be a major draw for voters this year.

Indeed, housing, like health care, should be a human right. But contrary to ruling-class ideology, homelessness is not a result of a lack of housing. A simple drive through Lewiston-Auburn reveals the dearth of empty, former mill buildings, just rotting away, unused. These buildings could easily be restored into housing for the poor and homeless.

But landlords and proptery developers are not in the business of providing homes to people who need one. They are in the business of making money. Sure, landlords often claim they have “no control” over how much they charge for rent — that such costs are determined by The Market. But this is nonsense. Landlords are business people — part of what Marx and Engels called the “petit bourgeois,” or “small bourgeois.” Like any capitalist, their aim is to make a profit.

Thus, homelessness exists in society for the simple fact that it is not profitable to rent to those with no money. And do not get me started on the cruel joke that is “affordable housing” — which is frequently unaffordable and substandard. Little wonder then, that the major affordable housing companies–Avesta Housing, Shalom House–have come out against Question 1. Like the misleadingly termed “nonprofit” sector, affordable housing exists to make a profit. It has nothing to do with providing housing for those who cannot afford it.

The anarchist collective, CrimethInc. is correct: We don’t have to live this way. Portland should not be the exclusive province of the wealthy and telecommuters “from away.” Working-class residents need to take our city back. If passed, Question 1 would be a significant gain for the working class.

As Owen Hill writes in a Feb. 25, 2016 story for the International Socialist Organization’s monthly newspaper, Socialist Worker, the left must fight “not just against what is wrong, but for our own vision of what is right.”

“[A]n organization fighting against gentrification and evictions cannot simply move from attempting to stop one eviction to attempting to stop the next,” Hill writes. “It has to also project a bigger vision of what housing justice looks like.”