Adam Marletta

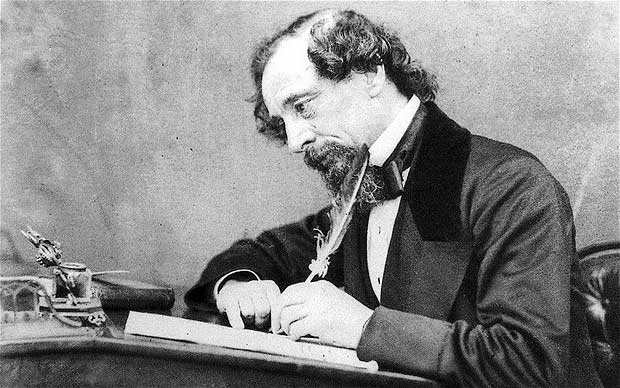

Charles Dickens, whose classic holiday tale, A Christmas Carol is ubiquitous on television and local theater stages this time of year, is one of my favorite authors. The celebrated British novelist had a keen insight into the arrogant mindset of the bourgeoisie that remains unrivaled in literature to this day.

Consider, for instance, when Ebenezer Scrooge is approached by two social workers who solicit him for a charitable donation for the poor. Upon rebuking them (“Are there no prisons? …No workhouses?”), Scrooge admonishes the social workers:

“I don’t make merry myself at Christmas and I can’t afford to make idle people merry. I help to support the establishments I mentioned. They cost enough. And those who are badly off must go there.”

“Many can’t go there; and many would rather die.”

“If they would rather die,” said Scrooge, “they had better do it and decrease the surplus population.”

Fast-forward to present-day GOP presidential contender, Donald Trump. When asked if he was “sympathetic” to minimum wage workers’ demands for a $15 minimum wage during a November 10 Fox News “debate,” Trump seemed to channel is own inner-Scrooge.

“I can’t be,” Trump flatly told moderator Neil Cavuto. “…Our taxes are too high…. Wages too high. I hate to say it, but we have to leave it [the minimum wage] the way it is. People have to go out, they have to work really hard, and they have to get into that upper stratum.”

Leaving aside the obvious factual errors of Trump’s response (both taxes and wages are notoriously low in the U.S. compared to other industrialized countries; likewise, Americans already rank among the hardest-working people in the world yet only a tiny privileged minority make into that “upper stratum”), his callous rhetoric toward the poor is virtually identical to Scrooge’s.

Turns out the capricious mindset of the rich has not changed much in the last 200 years.

Much as I enjoy A Christmas Carol it is unfortunate it is Dickens’ best known work, as the 1843 short story really only scratches the surface of its author’s literary talents.

Dickens’ novels following Christmas Carol, most of which originally appeared as serialized installments in magazines, featured intricately-woven plots, as well as darker subject matter. The classic Dickens storyline typically features dozens of characters—often, as is the case in Great Expectations and Little Dorrit, hailing from opposite social classes—whose fates are inevitably bound together somehow.

A master of wit and satire, Dickens’ stories often feature outlandishly cartoonish characters like the teacher Mr. M’Choakumchild from 1854’s Hard Times or the duplicitous Yes-Man, Uriah Heep from David Copperfield. Consider Dickens’ vivid description, as narrated by titular protagonist, David Copperfield, of Heep from the following passage:

“There I saw him, lying on his back, with his legs extending to I don’t know where, gurglings taking place in his throat, stoppages in his nose, and his mouth open like a post office… Afterwards I was attracted to him in very repulsion, and could not help wandering in and out every half hour or so, and taking another look at him.”

Dickens introduces Scrooge, likewise, as a “tight-fisted hand at the grindstone… a squeezing, wrenching, grasping, scraping, clutching, covetous old sinner.” Needless to say, Dickens was never too keen on subtlety.

But it was Dickens’ passionate humanization of England’s poor and working class, and his scathing indictment of the ultra-rich that truly secured his legacy not merely as a writer, but a social reformer as well.

Like George Orwell and Upton Sinclair, Dickens began his writing career as a newspaper reporter. His stories on the ills of London’s capitalist industrialization easily lent themselves to his literary exposes of child labor, homelessness, and the plight of the poor as depicted in Oliver Twist and Great Expectations.

Even Karl Marx took notice of Dickens’ socially-conscious writing. In an August 1, 1854 article in the New York Tribune, Marx praised Dickens as belonging to a “splendid brotherhood of fiction writers in England, whose graphic and eloquent pages have issued to the world more political and social truths than have been uttered by all the professional politicians, publicists and moralists put together.”

Dickens’ concern for the poor came out of his own childhood struggles with poverty. At the age of 12, Dickens was forced to leave school to work full-time in a rodent-infested boot-blacking factory after his father was sent to debtor’s prison. (Dickens would later denounce these prisons and the institutional criminalization of poverty, in 1857’s Little Dorrit.)

Indeed, Dickens’ own difficult childhood proved a near endless well of inspiration for his novels, nearly all of which feature child or young adult protagonists. For the leftist historian, Howard Zinn, who was greatly influenced by Dickens at an early age, this championing of the plight of children was something of a revelation.

“How wise Dickens was to make readers feel poverty and cruelty through the fate of children,” Zinn writes in his 1994 autobiography, You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train, “who had not reached the age where the righteous and comfortable classes could accuse them of being responsible for their own misery.”

To be clear, Dickens was not a socialist and it is not my intention here to paint him as such. While Dickens understood all too well the dehumanizing effects of capitalism, neither his novels nor his nonfiction writing offer anything in the way of an economic or political alternative. Indeed, the character of Madame Defarge, a bloodthirsty revolutionist from A Tale of Two Cities, whose motives have more to do with pure vengeance than any real political agenda, seems to hint at Dickens’ ultimate fear of a violent working class uprising.

In the place of revolution, Dickens stressed a generic Christian kindness, social reforms, and, in the case of Scrooge, philanthropic charity from the wealthy. (A socialist re-imagining of A Christmas Carol would perhaps see Bob Cratchit organizing his fellow workers to forcibly wrest Scrooge’s business and wealth from him. Come to think of it, somebody should really write that book…)

These limitations of political vision aside, one is hard-pressed to identify a contemporary author who shares Dickens’ keen sense of social outrage.

And this is why Charles Dickens’ work still resonates in our own time. Today, we find ourselves living in hard times not unlike those that defined Dickens’ Victorian England. In the wake of late-stage capitalism, and Wall Street’s trashing of the global economy, we are witnessing an unprecedented gulf between the rich and the rest of us. According to Oxfam, the richest one percent are currently on track to own more wealth than the rest of the world. This is a scale of global inequality the charitable organization calls, “simply staggering.”

Perhaps David Copperfield‘s perpetually unemployed Mr. Micawber best sums up the plight of the working class:

“Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure nineteen-six, result happiness. Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure twenty pounds ought and six, result misery.”

Dickensian Days Are Here Again: An Homage to Charles Dickens

Adam Marletta

Charles Dickens, whose classic holiday tale, A Christmas Carol is ubiquitous on television and local theater stages this time of year, is one of my favorite authors. The celebrated British novelist had a keen insight into the arrogant mindset of the bourgeoisie that remains unrivaled in literature to this day.

Consider, for instance, when Ebenezer Scrooge is approached by two social workers who solicit him for a charitable donation for the poor. Upon rebuking them (“Are there no prisons? …No workhouses?”), Scrooge admonishes the social workers:

Fast-forward to present-day GOP presidential contender, Donald Trump. When asked if he was “sympathetic” to minimum wage workers’ demands for a $15 minimum wage during a November 10 Fox News “debate,” Trump seemed to channel is own inner-Scrooge.

“I can’t be,” Trump flatly told moderator Neil Cavuto. “…Our taxes are too high…. Wages too high. I hate to say it, but we have to leave it [the minimum wage] the way it is. People have to go out, they have to work really hard, and they have to get into that upper stratum.”

Leaving aside the obvious factual errors of Trump’s response (both taxes and wages are notoriously low in the U.S. compared to other industrialized countries; likewise, Americans already rank among the hardest-working people in the world yet only a tiny privileged minority make into that “upper stratum”), his callous rhetoric toward the poor is virtually identical to Scrooge’s.

Turns out the capricious mindset of the rich has not changed much in the last 200 years.

Much as I enjoy A Christmas Carol it is unfortunate it is Dickens’ best known work, as the 1843 short story really only scratches the surface of its author’s literary talents.

Dickens’ novels following Christmas Carol, most of which originally appeared as serialized installments in magazines, featured intricately-woven plots, as well as darker subject matter. The classic Dickens storyline typically features dozens of characters—often, as is the case in Great Expectations and Little Dorrit, hailing from opposite social classes—whose fates are inevitably bound together somehow.

A master of wit and satire, Dickens’ stories often feature outlandishly cartoonish characters like the teacher Mr. M’Choakumchild from 1854’s Hard Times or the duplicitous Yes-Man, Uriah Heep from David Copperfield. Consider Dickens’ vivid description, as narrated by titular protagonist, David Copperfield, of Heep from the following passage:

“There I saw him, lying on his back, with his legs extending to I don’t know where, gurglings taking place in his throat, stoppages in his nose, and his mouth open like a post office… Afterwards I was attracted to him in very repulsion, and could not help wandering in and out every half hour or so, and taking another look at him.”

Dickens introduces Scrooge, likewise, as a “tight-fisted hand at the grindstone… a squeezing, wrenching, grasping, scraping, clutching, covetous old sinner.” Needless to say, Dickens was never too keen on subtlety.

But it was Dickens’ passionate humanization of England’s poor and working class, and his scathing indictment of the ultra-rich that truly secured his legacy not merely as a writer, but a social reformer as well.

Like George Orwell and Upton Sinclair, Dickens began his writing career as a newspaper reporter. His stories on the ills of London’s capitalist industrialization easily lent themselves to his literary exposes of child labor, homelessness, and the plight of the poor as depicted in Oliver Twist and Great Expectations.

Even Karl Marx took notice of Dickens’ socially-conscious writing. In an August 1, 1854 article in the New York Tribune, Marx praised Dickens as belonging to a “splendid brotherhood of fiction writers in England, whose graphic and eloquent pages have issued to the world more political and social truths than have been uttered by all the professional politicians, publicists and moralists put together.”

Dickens’ concern for the poor came out of his own childhood struggles with poverty. At the age of 12, Dickens was forced to leave school to work full-time in a rodent-infested boot-blacking factory after his father was sent to debtor’s prison. (Dickens would later denounce these prisons and the institutional criminalization of poverty, in 1857’s Little Dorrit.)

Indeed, Dickens’ own difficult childhood proved a near endless well of inspiration for his novels, nearly all of which feature child or young adult protagonists. For the leftist historian, Howard Zinn, who was greatly influenced by Dickens at an early age, this championing of the plight of children was something of a revelation.

“How wise Dickens was to make readers feel poverty and cruelty through the fate of children,” Zinn writes in his 1994 autobiography, You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train, “who had not reached the age where the righteous and comfortable classes could accuse them of being responsible for their own misery.”

To be clear, Dickens was not a socialist and it is not my intention here to paint him as such. While Dickens understood all too well the dehumanizing effects of capitalism, neither his novels nor his nonfiction writing offer anything in the way of an economic or political alternative. Indeed, the character of Madame Defarge, a bloodthirsty revolutionist from A Tale of Two Cities, whose motives have more to do with pure vengeance than any real political agenda, seems to hint at Dickens’ ultimate fear of a violent working class uprising.

In the place of revolution, Dickens stressed a generic Christian kindness, social reforms, and, in the case of Scrooge, philanthropic charity from the wealthy. (A socialist re-imagining of A Christmas Carol would perhaps see Bob Cratchit organizing his fellow workers to forcibly wrest Scrooge’s business and wealth from him. Come to think of it, somebody should really write that book…)

These limitations of political vision aside, one is hard-pressed to identify a contemporary author who shares Dickens’ keen sense of social outrage.

And this is why Charles Dickens’ work still resonates in our own time. Today, we find ourselves living in hard times not unlike those that defined Dickens’ Victorian England. In the wake of late-stage capitalism, and Wall Street’s trashing of the global economy, we are witnessing an unprecedented gulf between the rich and the rest of us. According to Oxfam, the richest one percent are currently on track to own more wealth than the rest of the world. This is a scale of global inequality the charitable organization calls, “simply staggering.”

Perhaps David Copperfield‘s perpetually unemployed Mr. Micawber best sums up the plight of the working class:

“Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure nineteen-six, result happiness. Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure twenty pounds ought and six, result misery.”